Eulogizing Joan Didion in the New Yorker, Zadie Smith paid her debt of gratitude for Didion’s unapologetic prose.

It was the authority. The authority of tone. There is much in Didion one might disagree with personally, politically, aesthetically. I will never love the Doors. But I remain grateful for the day I picked up “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and realized that a woman could speak without hedging her bets, without hemming and hawing, without making nice, without poeticisms, without sounding pleasant or sweet, without deference, and even without doubt.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf offers a similar insight about women who write. It is a miracle, she declared in this essay that began its life as a lecture, that women, who so often battle a world that does not want to listen to them, can find a way to express their genius—their unique contribution to the literary conversation—in a manner entirely authentic to themselves.

It is one thing to shout over the voices telling you to be quiet and make yourself heard in spite of them. It is quite another to speak as though they did not exist at all: to not allow oneself be pulled into the dialogue the voices have constructed for you, but to build your own. Have your own dialogue in your own play. Men are allowed to do this in the sanctum of their own interior creative garden. Women authors, Woolf argues, have to strive to achieve that same sanctuary for their own creativity. In the great ones, she said, you can’t see a hint of that striving. They write with the confidence of an author who knows that what they have to say is worth reading.

Unlike Virginia Woolf or Joan Didion, Anne O’Hare McCormick is not a household name. But she should be.

She was a woman of firsts: most notably, in 1937, Anne was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize solo—a student at Columbia won a one-off category with a fellow (male) student two decades before her—for her work covering the growing unrest in Europe for the New York Times. She was the first woman on the New York Times’ Editorial Board, and, perhaps, the first woman who began her career while traveling with her husband and ended it with her husband traveling for hers.

“Verbose Annie” as her editors called her, could perhaps be invoked as the patron saint of over-writers. Don’t kill those darlings, just dress them up real nice and make them so pretty, they’re indispensable. She could probably never depose Didion as the queen of stiletto-sharp sentences, but her essays ooze with insight: the sort of anecdotal analysis that appears effortless with much-practiced craft.

In her gripping dispatches for the Times, she plays off her reportage as the observations of a woman running into stories in the street.

“Crises were popping all over Europe at the time, so it isn’t strange that I bumped into a few,” she wrote.

But she is no ordinary writer, stumbling her way into stories. She has insight.

A dispatch from Bavaria in March 1936, three years after Hitler’s rise to power, is chillingly contemporary:

“Like its models [Italy and Russia], the Third Reich is that latest form of absolutism, the party-State; but whereas communism has universal aims and fascism is aggressively nationalist, neither system presumes to base policy, law, religion and economics on the idea that the state is a race or the race a State, with all exclusiveness and inclusiveness implicit in that extraordinary notion.

“Totalitarianism in Germany differs from the wide pretensions of similar regimes by going deeper; in addition to the blank ballot it requires also a blood test, a proof of conformity. The nation is conceived as a ‘blood brotherhood.’

McCormick noted that in one year, the proportion of students going to their church’s school and the state school reversed entirely: 35,000 (60%) in church schools one year, 35,000 in state schools the next. She saw how effectively the Hitler Youth recruited the young through peer pressure.

She spoke lightly about the barriers that she and her female contemporaries faced newspaperwomen. “We had tried hard not to talk—meaning too much—but just to sneak toward the city desk and the cable desk, and the editorial sanctum and even the publisher's office with masculine sang-froid,” she said.

Her obituary lauded the derring-do that propelled her to becoming not just a member of foreign correspondents, but a leader among them:

In the course of her brilliant newspaper career she became the expert the experts looked up to. Although she had no formal, professional training for newspaper work, she schooled herself for years before filing her first cable.

James’ father gave me a book of her essays covering the Vatican over three decades—from 1921 to 1954. She wrote a great deal about the papacy as it was entering a very important new phase of its life.

We so often reduce popes to their personalities—that one is conservative, that one is liberal, that one mean, that one nice. And, while she is a sharp observer of the varying demeanors of succeeding pontiffs, she also highlights the consistent new role the papacy carved for itself in the modern world. On the chessboard of European politics, each pope, no matter how different, occupies the same square.

The popes, so recently denuded of the Papal States, were finding new modes of interacting with the commonweal. The pope became first and foremost a spiritual leader of an ecclesial flock that spanned the entire world. Although his kingdom was reduced to Vatican City—officially, in 1929—the new media ecosystem that Anne herself participated in broadened the pope’s daily audience far beyond St. Peter’s Basilica.

In a power-hungry world of Nation-States, dictators, and iron rule, the papacy was emerging as a symbol of a different sort of power. “The Pope spoke as casually and confidently of ‘the help of God’ as the French speak of the Maginot Line,” she wrote in 1939 of the new Pope Pius XII. In the midst of materialism, the Vatican offered spiritual consolation, Anne realized.

Although she is not a prophet, Anne had an eye for the spiritual reality under the facts. She defended Pius XII from those blustery Westerners who critiqued the Pope for calling for anything less than a “total victory.”

History has certainly proved that perhaps firebombing cities, crushing the livelihood of one’s enemies and bringing a country to its knees, does not, in fact, lead to peace. Rather, the fascist hat is simply passed across the table to the victors. If we look at our violent and fractured country, prey now to the whims of one man—as Anne wrote of Hitler’s Germany—it seems hard to argue against Pope Pius XII’s prescience in cautioning world leaders to think of peace as a call to right relation within and between nations rather than domination over the enemy. Perhaps Pius was considering what the world would look like after the Cowboys of the West Marshall-Planne their way across Europe. What would it take to create a world of dignity after the violations and cruelties of the Holocaust? Certainly, it would take more than Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Writing about Trump’s inauguration in the London Review of Books, David Runciman noted the cost of Trump’s self-involvement. He highlights the civil and political cost. I might call it a spiritual cost: but really we’re talking about one potato with two names.

Perhaps some would argue the United States is not a project of humanist ideals and transcendence, but rather a greedy land grab, and that corporations have been considered persons in the eyes of the law before women or Black Americans obtained their equal rights to men or corporations, perhaps it is true that blatant self-interest and scraping the earth dry for whatever pennies it can make an already very rich man is the DNA of America—perhaps all this is true: America is a scam.

Well, we don’t un-scam ourselves by electing a scammer in chief. You can’t regain some sort of shared belief in a shared project by taking as our leader a man who can’t believe in anything beyond his own enlargement. “There is nothing that Trump can’t reduce to his level,” Runciman writes. No matter how ineffective your school is, insipid your curriculum, or uninspired your teachers are, you won’t learn anything new if you put the class clown in charge.

“The survival of the Church is connected to the survival of democracy,” Anne wrote of Pius XII’s concern for Europe in the war. That was a pretty stunning development for a Church that for several hundred years had insisted that the Church needed a Catholic king with a confessional state to ensure the practice of religion. The rise of the iron State, which tolerated no dissent and allowed religion insofar as it served the state, made it seem that rebellious Democracy was perhaps a better friend to the Church than previously conceived.

Anne called it: “the new phenomenon of the insatiable State, which lives by consuming everything, sees in every contrary opinion a threat to itself and loses all sense of measure or limit.”

Perhaps the state is not supposed to be a source of transcendence at all—Dorothy Day, for instance, would certainly find transcendence in the state a laughable idea. Ahat that means is that the state has to make itself smaller in order to allow sources of transcendence to have cultural real estate.

We are ruled by men who, by definition, avoid accountability. That is troubling in a democracy, when the ruling systems are, by definition, supposed to be accountable to the demos—the people. This is troubling in a deeper way, because, ultimately, a human is the being who stands before God, accountable for who she is and what she has done with her life. Even if you are good ol’ secular humanist, wary of a higher power, you could at least acknowledge that to be human means to be accountable to the forces that made you, which you are a fruit of but did not invent. You could at least stand humbly before the long line of ancestors that go before us, that have made the world we live in, much of it for ill, but much for good, as well.

You can’t actually reduce the world to your own ego, try as we do here in the U.S. of A.

One thing I have noticed about American Catholics is that we seem very eager to find in our faith support for the law of the land. “Yes the catechism says we can regulate xyzr,” “Yes, you can deport people,” “No you can’t,” etc., etc. on and on.

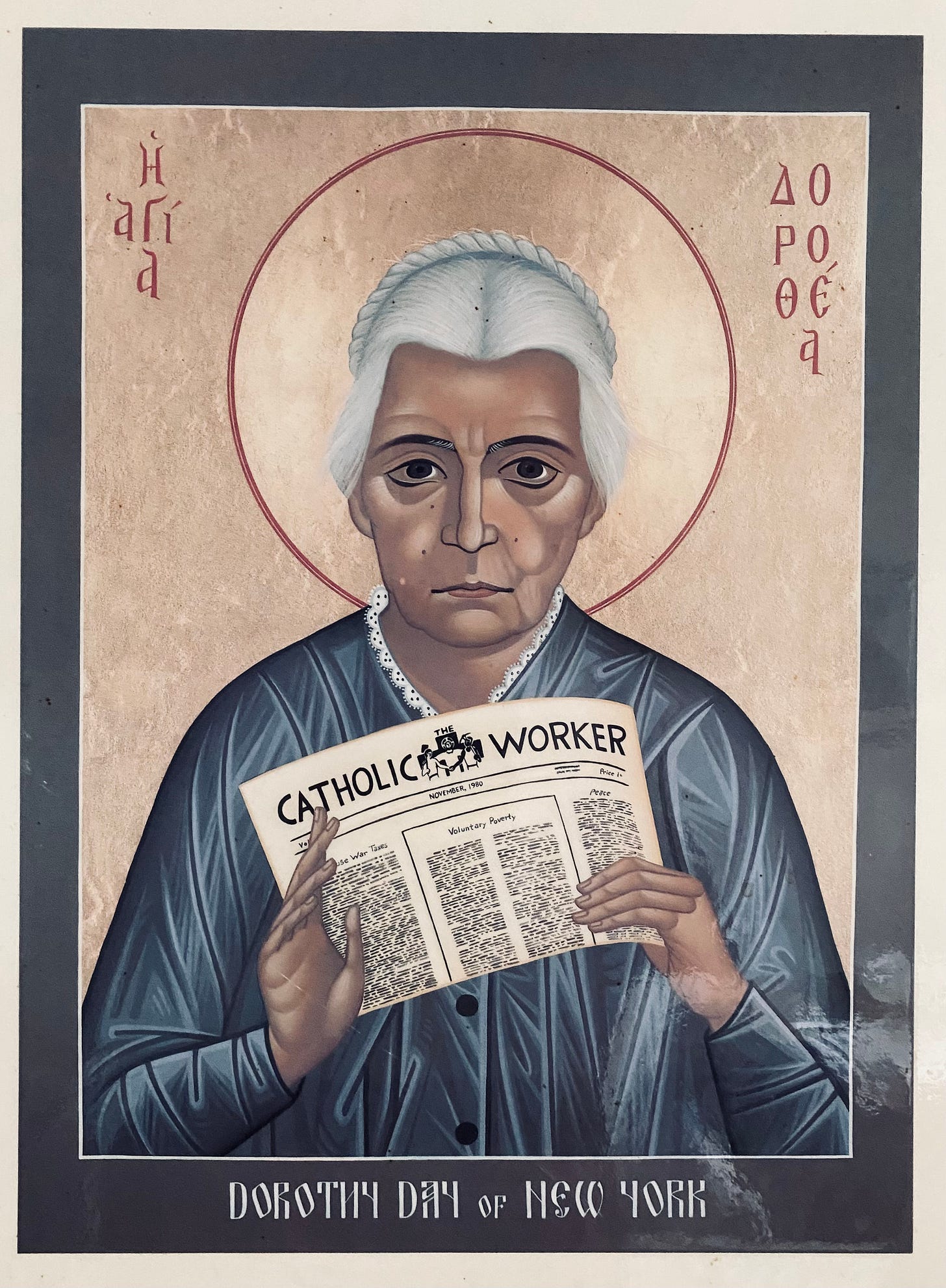

I find refreshing moral clarity in saints like Dorothy Day who, unlike Anne O’Hare McCormick, is not confused about the alignment of the American State and the Gospel of Jesus Christ. While they may occasionally agree on points—and let’s celebrate that—Day did not waste her time on something so fragile, corruptible and inconsequential as the state.

She didn’t need to find the Gospel proof text for a specific American belief. She simply got busy with the Gospel: a Gospel that demands every second of our day and every inch of our lives. Choosing the Gospel doesn’t mean that you don’t try to make a more just world or make the lives of your neighbor better, in fact, what it means is that you finally have the right tools for the job.

Because the Gospel reminds us that we are accountable to the force that made us and to the people we come from and depend on each day: and that force is love, which made this whole broken world to begin with, which is much more than ego can say.

“Our recent secretary of agriculture remarked that ‘Food is a weapon. […] Here we have an example of men who have been made vicious, not presumably by nature or circumstance, but by their values.”

— Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America

Sweet Unrest in the Streets

From the January edition of US Catholic, a piece on Beauty, through the lens of the story of the Apache Christ Icon that was stolen from a church last summer in Mescalero, New Mexico:

Beauty gives us a glimpse of the nature of pure being. It is one of the classical philosophical “transcendentals” (which also include goodness and truth). These transcendentals describe what it is that makes being being; in other words, what makes pure being—that is, God.

Anne Carpenter, a professor of theology at Saint Louis University, says it’s dangerous to conflate the church’s metaphysical or theological regard for beauty with the process of making art. Beauty, she says, is about the being of things, not the making of things. “It’s a faith affirmation that everything that exists is beautiful,” says Carpenter. “It is not a claim about which kinds of art are good and which kinds of art are bad or who has to make them and where they have to be from.”

You can read the entire article here.

As I was working on this piece and learning more about the artist of the icon, Robert Lentz, OFM, I realized that we actually had a great many copies of his icons here at the Harrisburg Catholic Worker, including a famous one many Catholic Workers are familiar with: Dorothy Day of New York (as seen above).

I had a very fun time talking about Antiqua et Nova — the new Vatican document on artificial intelligence—with my friend Bo Bonner at the Iowa Catholic Morning Show.