It occurs to me that friend groups, in late capitalism, are all about consuming together. You go out together, you go to theatre or the movies together, you book vacations together, you spend spend spend together, and there are tons of apps invented to help you spend money together more efficiently. Venmo, Splitwise, you can even pay someone on Facebook Messenger—although that might more often be a rando on Marketplace you’re buying a used Ikea table from.

Anyhow, I’ve just been thinking about how Millennials have always served two masters—that’s what a work-life balance means—and that, our jobs being for multinational corporations and our coworkers being all over the country and/or world, means that we have to create a community outside of the people that we do work with.

Plus, “work” is often so divorced from our day-to-day realities or the wellbeing of our own community. The Venn Diagrams between our communities and our work don’t overlap. These are broad generalizations, of course. But I think that sort of divide between work/ home, public/ private, social/professional is artificial. And, ultimately, detrimental.

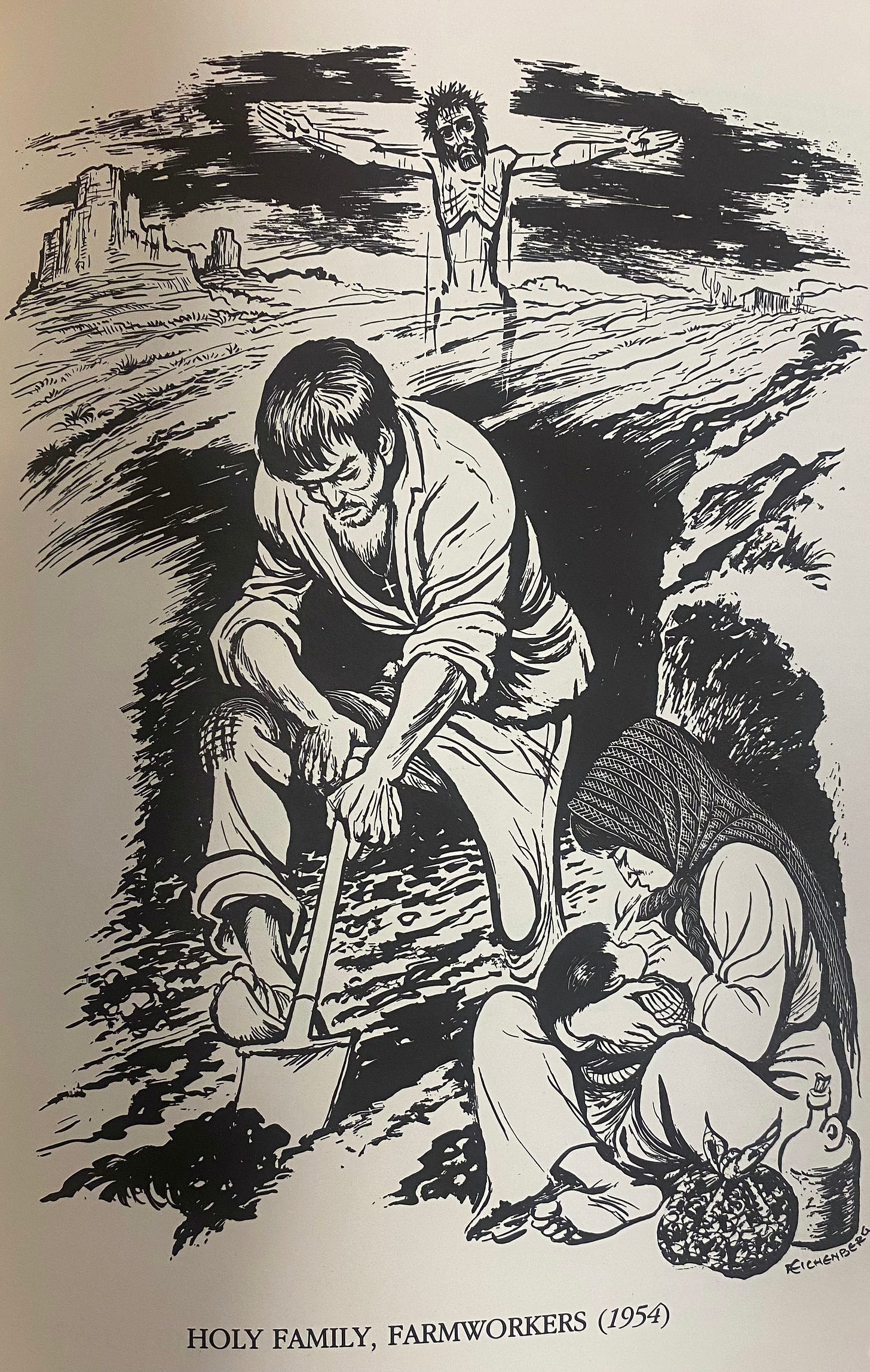

Work—labor—is supposed to produce something good. And it makes the most sense for a laborers work to benefit themselves, and their community, which they are a part of and which they belong to. That seems to be what labor is for. And, when labor is given over to a company that has nothing to do with—and sometimes is detrimental—to one’s community, we’re left with not many good intrinsic motivations for the labor. Wages become the only motivation. And wages have to be good for something.

The obvious answer—to previous generations—is that wages are good for buying a house (shelter, land, home, stability, being a natural human need) and starting a family. But those are not obvious uses for money to millennials, who have grown up in an economy where workers—from farmworkers, meatpackers, to McKinsey Analysts—are moved around for the greater profit of the company and the few who own it. Family, home, and children are not welcome intrusions into this labor environment. And so millennials spend their wages on rent in expensive cities and fun with friends.

This isn’t because millennials like avocado toast more than owning a home, but rather owning a home has become increasingly expensive, because it is better for companies’s bottom line to have laborers who do not own a home and are paying rent instead. And so it is better to share an overpriced avocado toast at brunch with friends than to be alone, which many people are.

This is not a finished thought. But I wonder if we were given more time away from our allotted eight hours of factory time—even if you’re your own boss, you live on the factory clock—if we could imagine a better way of organizing our lives than the unholy phrase of work/life balance.

Sometimes James and I overload a Hail Mary with more intentions than words in the prayer. But I’ve grown pretty profligate these days. My carbon emissions have doubled in the past week, as I have been lighting candles every day for a variety of intentions, each person, hospitalization, death anniversary, birthday old or new, getting their own candle.

I am surrounded by flames.

Gary, Indiana, does not have stoplights. They have been replaced with stop signs, because the city cannot afford the electricity. In 2018, it was going to take $90,000 over three years to replace the 25 traffic lights that weren’t working. 25 out of 93, according to CBS News. So Gary replaced most of them with stop signs.

As I pull up to another stop sign on my way to Michael Jackson’s childhood home, I wonder what the carbon footprint of traffic lights are.

Gary, Indiana, looks like a city that is slowly being overtaken by the natural world. I am encouraged, sometimes, when I see tree roots being uprooted by the persistence of cottonwood or oak trees’ root systems. It makes me happy that nature can, in the long run, overtake even concrete.

It doesn’t make me happy when I stub my toes or trip on it or think of the grandmothers in walkers or wheelchairs who are seeking the outdoors, drinking in the fresh (polluted) air, just as I am.

I know the empty lots are not magical, they’re a sign of racist neglect. They’re a sign of capitalism’s cruelties. But there’s something about them that whispers all the possibilities of untouched forest.

I overromanticize. I overromanticize Gary.

After one decade, my student loan debt has been sold. To another loan provider. Such is the American way.

I did a work of mercy on Saturday and it made me think of how isolated I’ve been this summer, in a haze of scholarship.

Christmas Gift Alert

If you need a gift for the theology major in your life who has everything, please consider preordering Gracie Mortbitzer’s Modern Saints book. Gracie reimagines the saints as little Gen Z hipsters (for the most part) and has a fresh, unique style of painting. I contributed two essays to this lovely project: I wrote on St. Olympias (my fellow John Chrysostom fangirl and soul sister, separated by a mere 1600 years) and St. Dominic. I didn’t know anything about St. Dominic when I took on the assignment, and I don’t really have much Dominican in my spiritual heritage—my saintly heroes wending more Franciscan, Benedictine, and Carmelite in nature—so learning about St. Dominic was a great introduction to a man whose gift to the world is less the theological rigor that his disciples have come to be defined by and more an expansive and overwhelming love for his neighbor in a pivotal age as his continent and Christianity itself were undergoing massive changes.

We are so afraid of change. I am afraid of change. We are all, to some degree—except for the saints.

As John Newman said, “while in a higher world it is otherwise, here below to live is to change—and to be perfect is to have changed often.” What we see in the saints are people unafraid to make the changes that love demands of us with each tomorrow. They do not live in yesterday.