While looking through my old Google Drive for a novel I started during the pandemic (I realized, as I pulled open the dusty old Google Doc, I had gotten 50,000 (terrible) words of it down on the page), I found a collection of writings from my old blog, all from the year 2015. Crazy that’s almost a decade ago. Much has changed. One of the interesting through-lines of questioning that I see in all this writing is a desire not to be separated from my neighbor. So much of our lives are predicated on separation from our neighbors. We do not even know how to approach one another as humans. See below:

The [washing of the feet] was a summary of [Christ’s] Incarnation. Rising up from the Heavenly Banquet in intimate union of nature with the Father, He laid aside the garments of His glory, wrapped about His Divinity the towel of human nature which He took from Mary; poured the laver of regeneration which is His Blood shed on the Cross to redeem men, and began washing the souls of His disciples and followers through the merits of His death, Resurrection and Ascension.

—Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, Volume II

Can any body body body help me help me help me

Can any body body body help me help me help me

—Man at 51st Street Station on the 4/5/6 Line

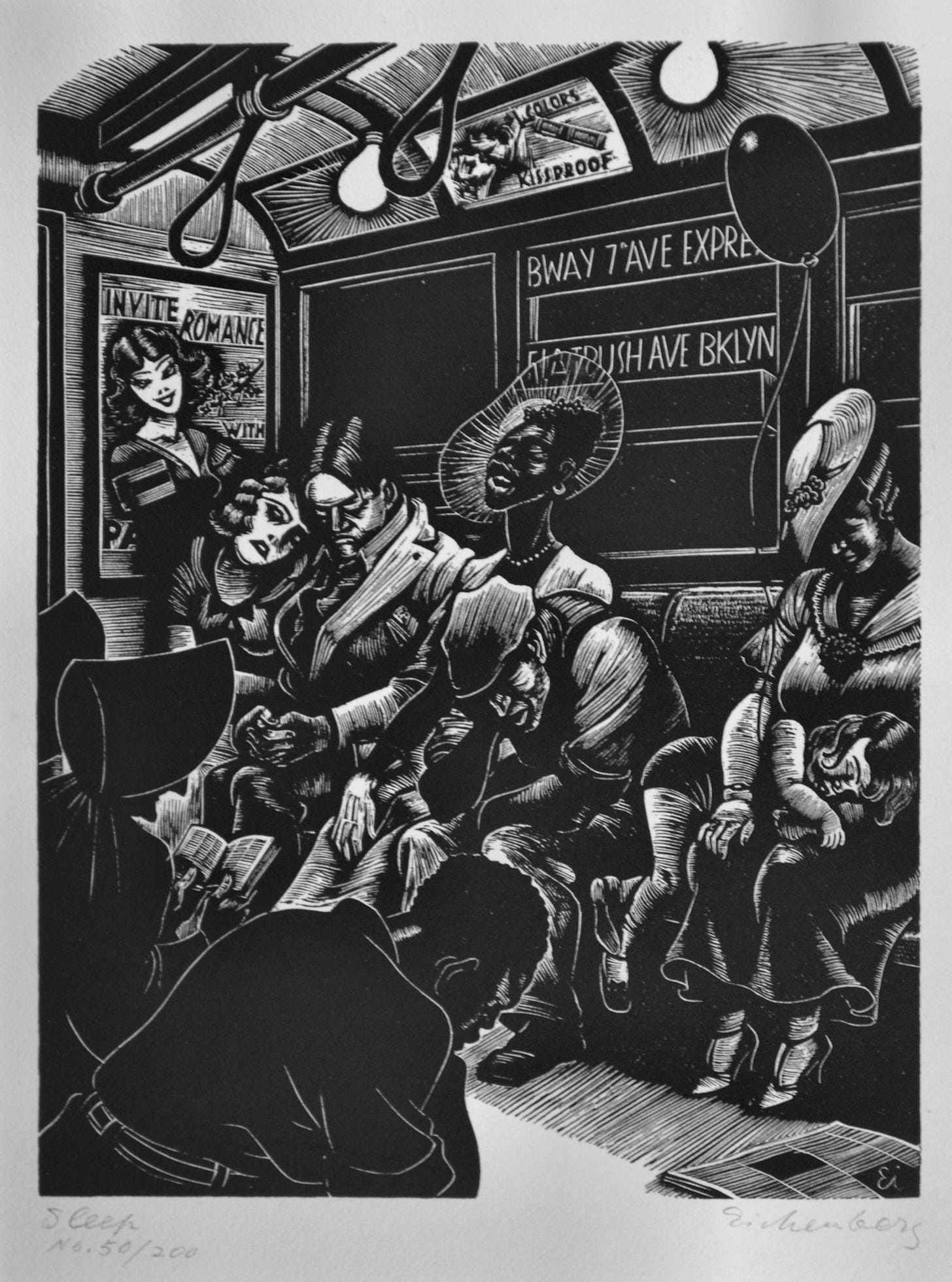

One of the most challenging aspects of living in a city is running into people who are asking for help—day in, day out—in never-ending waves. Each day, you encounter one of your brothers and sisters who is crying out for your assistance: they are on street corners, in subway stations, in the train cars, on buses.

It is overwhelming and discouraging to be surrounded by so many people who are all so helpless, who are discouraged or desolate. It is discouraging, but perhaps what is even more discouraging is how easily we walk by them. I do it, just like everyone else. But, what shakes me to my core is the nagging pull at my heart and mind that says: this person is an image of God. This person is Christ to you. This is your brother and sister and you are walking right by them, leaving them as hopeless as you found them. I think that we are able to do this so easily is that everyone else is doing it. We've created a culture of weak, cowardly comfort: of walking right by those in trouble, instead of walking up to them, or walking with them. As we watch everyone else walk right by them, we, too, turn our backs on them and deafen our ears.

Yet, there is a quiet movement of people who do not walk right by these people. A silent band of humans who reach out and answer these people's pleas: the business man sharing a Nutri-Grain bar with a man in Penn Station, kneeling in front of him and listening to his story; a father with his children on the S train, handing a man a $20 bill and a blessing; a couple inviting a young man into Starbucks with them—these people are reaching out past complacency to care for the people around them. They are responding to the world with honesty and an authentic embracing of reality: this person is Christ to me. I will treat them as I would Christ. Their example is an inspiration and invitation to join their ranks. Their example is a quiet protest against the norm of ignoring those in need. It whispers naggingly that we can either chose this simple heroism or chose complacency—we are not forced into complacency—it is a choice.

Also, I find myself inspired by conversation with my fellow thoughtful friends who are now young professionals in cities, who wrestle with these encounters each and every day.

How do we do this? How do we live out this very uncomfortable but ultimately very simple call to love each person that we meet? We find the answer is very easy, but takes a lot more strength than might be expected to put into practice.

After one such conversation, I found myself a few days later on a train car that was bombarded with humans clamoring for my intention. With the words of my friend stinging my ears, I found myself reaching into my purse into a small little pocket of loose change. But even more demanding than that: I always maintain that the Christian life is annoying, because it cuts into my reading time.

Well, I got to put that pithy little proverb into action. As I was reading Jesus of Nazareth (the first volume by Papa Benny XVI) on the subway, I noticed a seat open on the crowded car, so I squeezed into it. The gentleman to my right moved to make more room for me, and as he did so, he bumped me with his elbow. He apologized; I smiled a forgiveness. He took his earbuds out and asked: "What are you reading?" I, practiced in the ways of the city and having learned the hard way that friendliness is unfortunately usually rewarded with vulgar invitations and insinuations, respond, uninvitingly:

"A book."

Unfazed, the man continued to ask about the book: in a very respectful, but insistent way. Lord help me, I thought. I just wanted to get back to my book.

But I was reading a book about Jesus. So I couldn't very well put on my stone-cold bitch exterior and send this man on his way, as I usually do. One just can't act like a bitch when reading a book about Jesus. There was something about the honesty of the moment that demanded authenticity. I was reading a book about a someone who could also reveal Himself to me through this person next to me. And how could I ignore the invitation in the voice next to me? How could I ignore the desire to speak with another human, to be acknowledged and listened to, to be paid attention to, if only for a brief train ride? How could I ignore that invitation, while I was reading a book about a Person who makes that invitation to me every day? So I closed the book cover and turned to encounter the image of Christ talking my ear off next to me.

I would rather encounter Christ in the safe and orderly words on the printed page. I would rather find him neatly contained, tamed, inside a tabernacle. But the lion of Judah is far from tame, and I find that he is nearest to me in the wild of this unbearable city. He is found in the uncomfortable, sordid, painful moments when I decide to look up at the person next to me and walk alongside of them in their world, to empathize with their life, if only for a moment.

"Not one word [is mentioned] about whether you belonged to the church, whether you were baptized, whether you celebrated the Eucharist, whether you prayed. […] Not one doctrine, not one specifically religious act of worship or ritual turns out to be relevant to the criterion for the last judgment. The only criterion for the final judgment is how you treated your brothers and sisters.”

—Michael Himes, Doing the Truth in Love