“where does cruelty begin and end?”

— Dorothy Day, 1956

These days, I’ve started biking down the State Street bridge into Harrisburg, rather than Market Street. From the State Street bridge you can see the bluffs to the north overlooking the Susquehanna River. You can see mountains. The city’s concrete doesn’t seem so all-encompassing. You can remember that you live in Creation, and there is an embarrassment of beauty being showered on you.

Allison Hill, in Harrisburg, is not beautiful. The buildings are beautiful, which makes me know that at one point, people cared about this place. People still do care about this place, but I guess what I mean is that once upon a time people with money cared about this place.

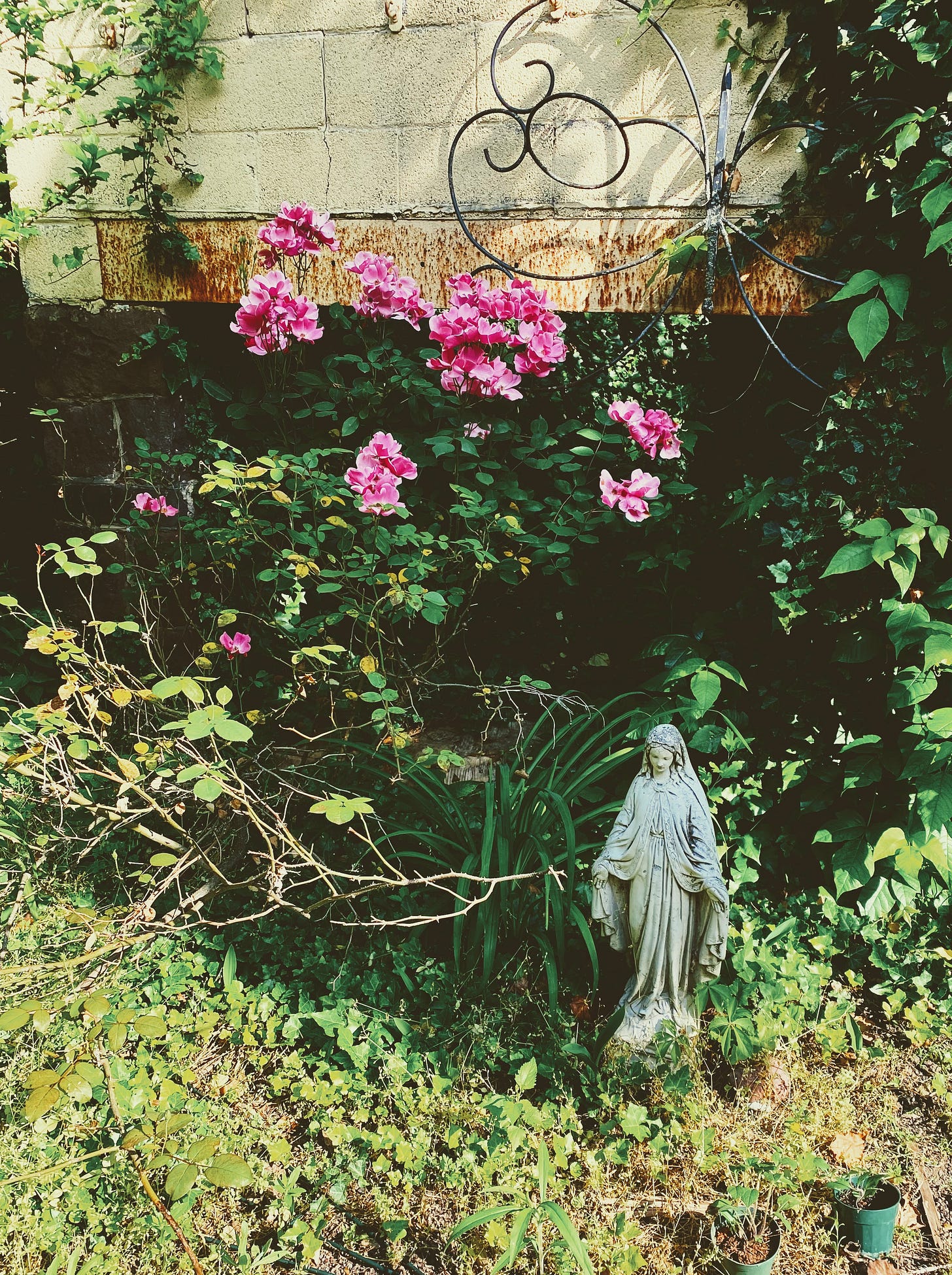

Allison Hill, aesthetically, is a harsh place—the buildings are crowded together like teeth in need of orthodontics, trash seems to rise up out of the ground like weeds, there are boarded up buildings and busted windows, power lines sag across the sidwalk. The concrete and asphalt have made this summer like an oven. There have been more than 25 days over 90 degrees since I moved here. I yearn for tree cover. If I had my way, all the concrete parking lots dragging out across Cameron Street would be green—parks, gardens, trees. I just imagine nature climbing south from those Susquehanna bluffs and re-taking the land we have so poorly used.

But, tonight, after the rain, the street was silent. Sun peaked out of the clouds. The world had been washed clean, baptized. I felt gentleness pouring through Allison Hill. The few people out walking were meditative, soaking up the cool weather and the colors of a cloud-speckled, rain-drenched summer evening. There were no cars speeding by to disturb the quiet. This is the opposite of Noah’s Ark, I thought: the rainstorm was God’s promise of salvation.

It is very hard, in a hard, concrete to find beauty. Sometimes the cruelty of the world and the harshness of the human heart and the systems humans have made to rule over one another feel so oppressive in their ugliness (as Dorothy Day writes in the editorial quoted above).

My grandmother, on her sunporch, had a large-print copy of Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land. Despite many of my J-school classmates reading it when it hit the bookstands in 2021, I had not read it. I wanted to the entire winter I spent on my grandmother’s sunporch, but the large print (which she needed as her eyesight failed) deterred me. Large print books are not an aesthetic reading experience.

But, as I was packing up books to bring with me from her house, I put the doorstopper of a book into a box. As I sat in bed with my fifth bout of COVID, I picked it up. Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See was one of my favorite books of 2017 (which I also read, come to think of it, at my grandmother’s house). Doerr excels at creating intertwining story lines that eventually bring me to big, fat, ugly crying at their denouement.

Cloud Cuckoo Land is very much about what it means to be a human in a very cruel and unfair world. About what it means to yearn for the beautiful when you have been given the ugly lot in light. It is about making something beautiful of your life not in the first or even second act, but in the final act, perhaps even the epilogue. It is about the cruelty of superstition, of ignorance, of world where might makes right, it is about the harm to the human spirit when life is treated as disposable, it is about our destruction of forests and what is lost when we tear down what is beautiful to increase market values. It is a call to make the choice to be gentle: to preserve the owls and the wilderness, to preserve old words and stories, to seek what is delicate, breakable, and fragile, even if the rest of the world decides it is dangerous or useless: that those things might be what save us.

Before I knew the Dostoevsky quote so loved by Dorothy Day—"the world will be saved by beauty”—I knew the Mother Teresa quote emblazoned on the wall of her orphanage in Kolkata: “Let us make something beautiful for God.” And I think that idea of making something beautiful, finely crafted, full of love: that seems like something all of us are capable of. It does not have to be a grand world-saving machine or program of action for an entire nation. All we can do is make what our hands touch and our hearts hold beautiful.

Some days, it feels like the darkness of the world is too much. As Doerr shows so beautifully, the world has ended multiple times: civilizations are lost to memories, names of kings and authors are forgotten and what seems permanent crumbles. There is no assurance that the little light we shine into the darkness will make any difference whatsoever. But I suppose that’s what faith means.