Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.

— John Keats, To Autumn

This morning, the trees in the park were already naked, littering the ground with dry brown leaves. The wind felt like November, which I suppose it nearly is. The golden mornings of autumn sunshine on yellow and red leaves were so brief this month they might have been skipped altogether.

Four days ago, I turned 30. There’s something about 30 that’s supposed to feel significant— as though, I suppose, you have arrived. Thirty-somethings drop the “young” in front of adulthood. Now, they are simply adult.

Generally, in your twenties, you collect signposts of stability, signs of arrival: weddings, home mortgages, babies, dogs, careers, five-year anniversaries in offices. Many of my friends have done so over the past decade. But much like I did at 20, I still feel very much en route, without any accoutrements of arrival.

In The Rock that is Higher, Madeleine L’Engle writes:

"I never want to lose the story-loving child within me, or the adolescent, or the young woman, or the middle-aged one, because all together they help me to be fully alive on this journey, and show me that I must be willing to go where it takes me, even through the valley of the shadow.”

If there is one thing I feel having reached my 30th birthday, it is very much in touch with the six-year-old in me who learned how to spell “yes” in French while reading Little Women, with the teenager who read while scootering around the cul-de-sac or backstage during matinee performances, and with the college student feeling lost and overwhelmed. Their memories mingle with the 25-year-old distributing wisdom and candy to college students from the comfort of a futon, the 27-year-old struggling through heartbreak, and with the Renée of today, cultivating community and love, trying to illuminate and clarify a chaotic world through words.

I don’t know that I feel more established or more certain than any of those past versions. I feel less like I have gone forward and more that I have gone deeper—into the shadows within me, into unexamined corners of my heart, into old and new habits of being. And holding each of these past selves within me, knowing that there isn’t a corner of myself that cannot be exhumed and illuminated, knowing that the destination of the journey is, in fact, deep within — each footfall on the unknown path forward feels surer.

Affectionately yours,

Keats in the Sheets

“There is no greater Sin after the 7 deadly than to flatter oneself into an idea of being a great Poet”— to Benjamin Robert Haydon, May 1817

— From the Blog—

Things Hang Together

… That January, I began a directed reading with Vittorio. Vittorio has the stature of Frodo, the visage of Harry Potter, and the magic of Merlin. My classmate and I squeezed into his office alongside shelves of books every Wednesday. We sat on folding metal chairs in the overheated 1970’s architectural atrocity of the faculty office building. And then we opened our books and were transported to Dante’s paradise or Dostoevsky’s St. Petersburg.

Vittorio had a set of hangers behind his office doors we would put our coats on. One of the hangers in Vittorio’s office was made of light maple-looking wood that would fall apart at the joined seams. Each time I showed up, I would take off my parka or jacket, I would reach for a hanger, and I would pick up the busted wooden hanger which would fall apart in my hands. We would laugh, and I would put the two sides back together again. Then hang my coat on it. Repeat. It became sort of a recurring joke. A joke whose setup was its punchline—the simple comedy of insisting that something broken, isn’t.

Read the full post here.

Keats in the Streets

“I am however young, writing at random—straining at particles of light in the midst of a great darkness” to George & Georgiana Keats, May 1819

—Sweet Unrest stylings out in the world—

If Christ has one message, it’s that we are called to embrace what’s weak rather than to subjugate it. Whether that’s our own flimsy nature, a child, the homeless man sleeping on the subway floor — we learn to love like most God when we look on what is more fragile and more vulnerable than ourselves with tenderness.

For some reason (Augustine has some ideas about this!) this embrace of weakness is very hard for us. This question of what to do with weaknesses is at the heart of so many of our social debates in the muscular, individualistic United States. So here is my piece on the impossibility of addressing the problem of abortion without addressing sexism, two phenomena, I would argue, that have co-existed symbiotically since the beginning of time.

Pro-life Catholics: You can’t end abortion without taking on the patriarchy.

…Most Americans believe there should be some legal limits on abortion but that it should be available for women legally. So what are the 57 percent of Americans who believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases seeing that pro-life Catholics are not?

Maybe what supporters of abortion in the United States recognize is how deeply patriarchal attitudes about sex are ingrained in our culture, how little control women have over when and how they have sex—even with partners they love. Maybe they see the immense pressures a patriarchal culture places on women to have sex on a male timeline and its negative effects on women. Perhaps they are concerned about the horrifically high rates of domestic violence in this country. And the disturbing statistic that 1 in 5 American women will, at some point in their lives, be raped.

The Catholic Church has made it clear it stands in solidarity with unborn life. But in the three decades I have been a part of the church, I have seen it do little to address the abuse of women.

You can read the full essay here.

-

All Saints Day and All Souls Day are two of my favorite feasts of the liturgical year. Partially because I am constantly asking myself what happens after we die. These questions are primarily logistical—what are the mechanics of the afterlife? Where, physically or materially speaking, does a soul go without a body? Where (geographically) is God on the other side of death and how are we present there?

These two eschatological feasts remind us that the answers to these questions are right in front of us. To be baptized into Christian community means that we are members of Christ’s mystical body—the love that we celebrate in the liturgy and the love in which we dwell among in the communion of believers is the love that persists on the other side of the grave. We already participate in what endures. And on these holy days, we remember those we love in the parts of our communities we can no longer see or touch.

Accordingly, I was delighted when Scott at Our Sunday Visitor asked me to write a piece that grappled with the questions of love and death on the occasion of All Souls Day.

COVID-19, All Souls Day and experiencing the grief of Job

“Why is light given to the toilers, / life to the bitter in spirit? / They wait for death and it does not come; / they search for it more than for hidden treasures.” — Job 3:20-21

What good is hope, Job asks, for those who have been struck by death? What comfort is available to the suffering?

At the beginning of the Book of Job, he mourns the unthinkable devastation that has deprived him of his livelihood — even of his children — and has afflicted him with sores all over his body. Thus begins Job’s story, which poses humanity’s most fundamental religious question: How does a believer reconcile a God who is good with the experience of suffering?

Scholars believe that the Book of Job may be one of the most ancient books of the Hebrew Scriptures. But the question it poses is one we still grapple with today: How can we believe in God’s goodness when we seem to suffer disaster at random?

You can read the full reflection here.

Keats Reads

“The Literary world I know nothing about” to George & Georgiana Keats, Feb 1819

—Highlights from the Good Reads shelf—

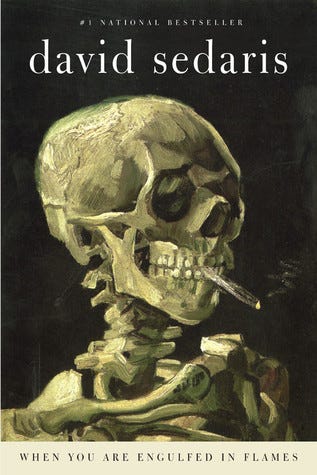

While pursuing the dusty shelves of the used bookstore on Wednesday on the phone with Denise, I stumbled across my favorite David Sedaris book of all time.

When You are Engulfed in Flames

I have been re-reading it on my bench each morning, inevitably laughing out loud just as I did while listening to it in my apartment four falls ago.

David Sedaris is a short-story writer whose mastery of the form is as idiosyncratic as it is precise. He can drag a bit out to absurd degrees, and just when you think he’s rambling or losing the plot, he doubles back to some kernel of poignant observation that he dropped several paragraphs earlier.

Sedaris is a true original — the form of his writing seems to perfectly incarnate his persona, his style is truly a unique manifestation of his being in the world (or at least is crafted to appear this way — a tautology).

Sedaris uses sardonic observational comedy to mine not-quite insights into human nature and self-deprecating insights into himself. His essays, although they mostly reflect on his life experience and mock his personal foibles, never slip into solipsism.

When You Are Engulfed in Flames includes the glorious paean to his crazy septuagenarian New York neighbor, Helen, in which he never processes guilt he does not feel over her death, his folksy account of coming out as a twenty-something, his hard-earned style commandments, and his account of quitting smoking in Japan which made me laugh so hard I wondered if it had induced a hernia.

Mr. Brown’s Bylines

“Brown, who is always one’s friend in a disaster, applied a leech to the eyelid, and there is no inflammation this morning though the ball hit me on the sight.” to George & Georgiana Keats, May 1819

—Pieces from good friends, and from writers whose words have been a friend to me—

Susan Bigelow Reynolds, “Going Gray,” Commonweal

Susan, an acquaintance of the Twittersphere, has penned an ode to grey hair as a sacrament of mortality that calls to mind the communion of saints who leave behind their own traces of corruptibility as sacramentals of immortality—and it is delightful.

November is the month of mortality—the month of saints and souls. God may remain confoundingly hidden, but saints leave trails of matter: bones and teeth and corpses that miraculously refuse to decompose, catacombed skeletons adorned with jewels, vials of blood and locks of hair, tunics and tilmas and roses out of season, and things stranger still—severed heads and eyeballs on a plate and candles that heal throat ailments. It’s little wonder that these November days give way to dark Advent longing for God enfleshed.

Read the full reflection here.

John Cavadini, “Augustine and Francis: The Saints of Laudato Si',” Church Life Journal

A beautiful reflection by a beautiful theologian, one I am proud to call a teacher, on the tender theological underpinnings of Laudato Si’.

What is there to rejoice among the worthless but necessarily to see worth there? But a different worth and a different value than the cash value, the value related to ownership and use. It is to see in each of them reflected and refracted back the poverty of the “all powerful” who can dispose of anything in whatever way he wills, but actually willed to come among us in our flesh, in the of a poor man, an alien dependent on the good will of others, and surrounded by other poor persons, he and the Blessed Mother and the apostles, insulted, cursed, dispossessed to the point of nakedness on the Cross, the Lamb of sacrifice, indeed, a worm and no man.

God almighty become a worm.

Read the full essay here.

Ciaran Freeman, “Review: Sally Rooney writes for millennials in a post-Catholic world,” America

I hate Sally Rooney’s novels and no one can convince me otherwise. Except, maybe, Ciaran, a fellow Emily Dickinson lover, who has almost convinced me to open up Rooney’s newest in this lovely review.

What does Rooney present as the alternative? Love. It is an idea her characters may have picked up on while in Rome. Beautiful World, Where Are You reads like a sexy, millennial novelization of Pope Francis’ “Fratelli Tutti.” Francis writes what could be a thesis statement for this novel in that encyclical: “Authentic and mature love and true friendship can only take root in hearts open to growth through relationships with others.”

Read the full article here.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too, —

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The redbreast whistles from a garden-croft,

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

— To Autumn, John Keats