Artists unmask the lie that man is a “being towards death”. We must certainly come to grips with our mortality, yet we are beings not towards death, but towards life.

—Pope Francis, Address to Artists, Sistine Chapel, 23 June 2023

He told them another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened.’ —Matthew 13:33

What is the Kingdom God that history is careening towards?

This morning, I wrote this question. This afternoon, I read Matthew 13 in a circle with four other Christians. And I laughed. All these parables answer my question: the kingdom of God is a mustard seed, yeast, a lost coin, a pearl of great price, a lion lying down with the lamb.

But the Kingdom of God is also not literally any of those things. So what is the kingdom of God? And how is it not like the kingdoms of this world? We really don’t know anything about the Kingdom of God. We know more about what it is not than what it is.

The recent joint document by the Orthodox-Catholic Dialogue discusses how the social imagination of the Church and of the world deeply have deeply impacted the structure and unity of the Church.

After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, the situation of the Roman Catholic Church in Europe was precarious. The new political regimes, even the restored monarchies, were secular states which claimed to maintain control of the Church, just as the former regimes had done. An example was the French concordat of 1801.

The Concordat of 1801 was a treaty between Napoleon and the Vatican which gave the French government the right to elect bishops and open seminaries, provided for the salaries of priests and bishops and condoned the state seizure of Church property. The concordat was revoked a century later, in 1905, when France announced the separation of Church and State. Anyhow, as you can imagine, that concordat was a game changer for the nineteenth-century Vatican, which was not interested in going the way of all flesh, as were so many ancién regimes.

The document continues:

Later on, to avoid state interference in ecclesiastical affairs, the papacy adopted the doctrine of the Church as a ‘perfect society’, meaning that the Church was an independent, autonomous, and sovereign society in her own sphere of competence, just as the state was sovereign in temporal affairs. The Church claimed to be invested with an original legal system, i.e. not derived from or bestowed by the state.

So the Church pulls back into its own separate realm, the cloister of religion, the domain of professional churchmen only, leaving the laity lost in the sea of the ordinary, which is ruled by secular powers and their iron love of money, and is no concern of the pure priests and the holy heirarchs.

Yet, during this exact time, Christians across the globe insisted that the Church was not for professionals, and the world was the arena of salvation history.

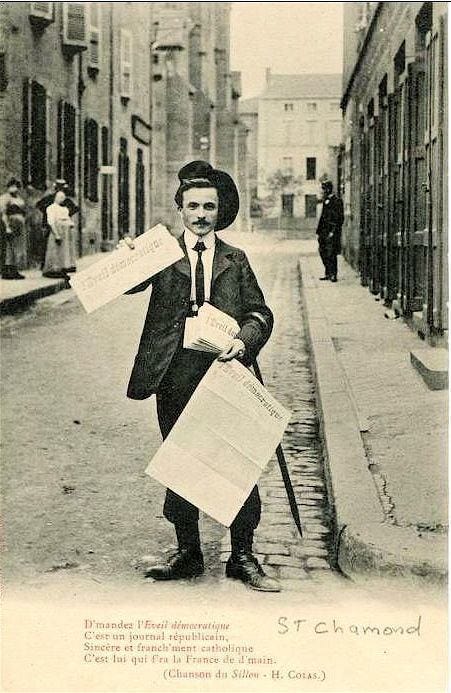

In a talk at the Abbey of the Genesse, in 1975, Dorothy Day speaks of the lay movements that sprung up in the century following the Concordat of France’s signing. Many of them in France itself. One of the chief fruits of that long nineteenth century in France that so influenced Notre Dame was, of course, a peasant scholar by the name of Peter Maurin, who was influenced by those movements.

Day said: “The source of our work was Peter Maurin who was influenced by what was suspect at the time: the writing of Emmanuel Mounier, the writings brought to us through Esprit, and Marc Sangnier and Le Sillon”

Those Frenchmen may not be household names for American Catholics the way Day herself is, but their influence upon Peter Maurin, Day, and, accordingly, the course of the Catholic Worker’s history was profound. Among their wide-ranging philosophies, the two chief lessons from Sangier and Mounier are first, the inextricably social imagination of the Gospel, and two, personalism.

But the Sillon had conveyed another message to [Sangnier]. Religion and everyday life were not two different worlds. Religion could only be lived in the midst of life.

Religion could only be lived in the midst of everyday life, Marc Sangnier and Le Sillon believed. And so we see lay Catholic action take shape—a rejection of the fencing off of the spiritual, a rejection of the de-incarnating the church from the world, roping off the sanctuary, and turning one’s back on the revolutions outside.

Life is overwhelming in its multifacet-ness. The more we know about the universe, the more we seem constrained by our particular location, by the limits of what we know when we stand somewhere singular. The uncertainty principle limits us to the particular, we seem cut off from the universal picture. So we wonder what we would know—or be—if we continued our trajectory down one road instead of others. The idea of multiple universes lingers in our imaginations.

But even less than multiple universes, it’s hard to know the right course of action in this world: one can take a different tack depending on the day. Do I challenge a loved one on their choices? Do I make space for them and listen? Am I seeing something true that they cannot? Are they seeing something from their perspective that I’m blinded to? Do I simply ask questions and love them? What position does one take toward another person?

We’re all searching for the right “take,” as they say on the web, to save us. That’s the anxiety of Twitter: journalists searching for the take, the opinion, the point-of-view that will unlock the truth.

It occurs to me one night in adoration, that the point of baptism is that we now know our vantage point. We know the ultimate trajectory of humanity, as Christians. We know our telos—in a spiritual sense—and the goal of human history—in an earthly sense. We are working for and building the Kingdom of God on earth. God will reign. The kingdom of God is the goal. What are we working for? The kingdom of God. What is it? Do we really know?

It has never existed yet—in this greedy, bloody world. But yet it already exists. We keep articulating it, trying to add to the mystery of it—it is found in every single bit of goodness that has ever dwelled inside a person. The mustard seeds. The pearls. The Kingdom of God does not exist in the far-off ways of goodness delayed. It is built of here and now. The small hazelnuts of goodness that bear witness to it.

That’s what Marc Sangier knew. And Peter Maurin. And Dorothy Day. A long line of disciples passing down a tradition of hope in the midst of darkness to us. The kingdom of God is within us, and it is just waiting for us to put it into action.

When the Gospel gets a social imagination, it is unstoppable.

Finally, Mounier gave Maurin and Day personalism—that necessary belief that puts the Gospel into action.

Personalism, as defined by Emmanuel Mounier, Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day is that radical belief that I am responsible for my neighbor—the thief, the robbed, and the Samaritan—all of them. “It is easy to delegate charity to others, yet the calling of every Christian is to become personally involved,” says Pope Francis.

We live in large cities, a fractured world, and a dirty rotten system, broken seemingly beyond repair. 48,000 gun victims a year, 600,000 homeless, 70% of Americans living paycheck to paycheck. Am I responsible for healing all of that? How can this be when I am only one little woman?

We can do only so little alone, we can do much more together. But we have to create a sense of co-responsibility as a community.

All last winter, and the year before, a woman who is extremely mentally ill slept on our church steps. The only other person who she would allow up there is our friend John. John—bless his soul—is the only other person in Chicago who loves the London Review of Books as much as I do and is an incurable hoarder, and his pile of Amazon boxes and bric-a-brac mushroomed at an exponential rate. His boxes of garbage and food pulled from dumpsters piled up like a Crusader fortress on the side of the church. A few more people came as the weather started to get warmer, and then a few more. And then the Church steps were an encampment of people, boxes, and carts.

Homeless people are no strangers from being ushered away from any space that offers repose—subway terminals, church steps, park benches. So they expect antagonism, and, unfortunately, once the antagonism starts, sides usually entrench themselves in their positions, rather than all working for the common goal of helping the sleepers find safe shelter.

How does a Eucharistic community respond to sleepers on their steps? Pope Francis says, in his message for World Day of the Poor:

In a word, whenever we encounter a poor person, we cannot look away, for that would prevent us from encountering the face of the Lord Jesus. Let us carefully consider his words: “from anyone who is poor”. Everyone is our neighbor.

A community of people who proclaim Christ crucified should have more to offer their homeless neighbor—who, our scriptures tell us, is the “least of these” in whom Christ dwells—than the anti-homeless architecture and attitude they meet on every corner of the city. We should have more to offer, and yet we don’t often know how to give more. We neglect taking personal responsibility because our efforts feel so insignificant in proportion to the need. Once we open the floodgates, we fear we will we drowned. And, alone, we will.

As Francis says, we are living in times that are not “sensitive to the needs of the poor.” We all feel pressure to get ahead, to adopt a more affluent lifestyle. “Haste, by now the daily companion of our lives, prevents us from stopping to help care for others,” Francis says.

But love is something we cannot live our day without, and we only love God as we love the one we love least. Pray for grace in the midst of “business as usual” and for all of our world-hardened hearts. Christianity is a story of failure, so the goal is to try, not always succeed.

The Eucharist does not live just in the tabernacle, but on every city street and every park bench. Religion can only be lived in the midst of everyday life, so we have a duty to our neighbor who is the temple of God even more than buildings made of stone. As Pope Francis says, “We cannot truly understand or live the meaning of the Eucharist if our hearts are closed to our brothers and sisters, especially those who are poor, suffering, weary or who may have gone astray in life.”

When the Gospel gets a social imagination, it is unstoppable.

In the first centuries

of Christianity

the hungry were fed

at a personal sacrifice,

the naked were clothed

at a personal sacrifice,

the homeless were sheltered

at a personal sacrifice.

And because the poor

were fed, clothed and sheltered

at a personal sacrifice,

the pagans used to say

about the Christians

“See how they love each other.”

In our own day

the poor are no longer

fed, clothed and sheltered

at a personal sacrifice,

but at the expense

of the taxpayers.

And because the poor

are no longer

fed, clothed and sheltered

the pagans say about the Christians

“See how they pass the buck.”

Hear Ye Hear Ye

Jerry at the Catholic Worker Dot Org is working on some big plans. If you are interested in receiving Catholic Worker news to your inbox, sign up here!

“Strikes Don’t Strike Me”

said Peter Maurin, who imagined worker-owned, cooperative newspapers, fired bosses, and the abolishment of wage labor.

I generally agree with him, but I can’t help but give a major kudos to Dan Latu (that’s my boi!) and the staff of Insider for taking action and walking off the job for thirteen days, to the staff of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and of course, the writer’s guild members.

Now let’s fire the bosses and start a cooperative.

Pope Francis’ Pitch for Embracing Poverty

Tobit, in his time of trial, discovers his own poverty, which enables him to recognize others who are poor. He is faithful to God’s law and keeps the commandments, but for him this is not enough. He can show practical concern for the poor because he has personally known what it is to be poor.

His advice to Tobias thus becomes his true testament: “Do not turn your face away from anyone who is poor” (4:7). In a word, whenever we encounter a poor person, we cannot look away, for that would prevent us from encountering the face of the Lord Jesus.

Let us carefully consider his words: “from anyone who is poor”.

Everyone is our neighbour.

Regardless of the colour of their skin, their social standing, the place from which they came, if I myself am poor, I can recognize my brothers or sisters in need of my help. We are called to acknowledge every poor person and every form of poverty, abandoning the indifference and the banal excuses we make to protect our illusory well-being.