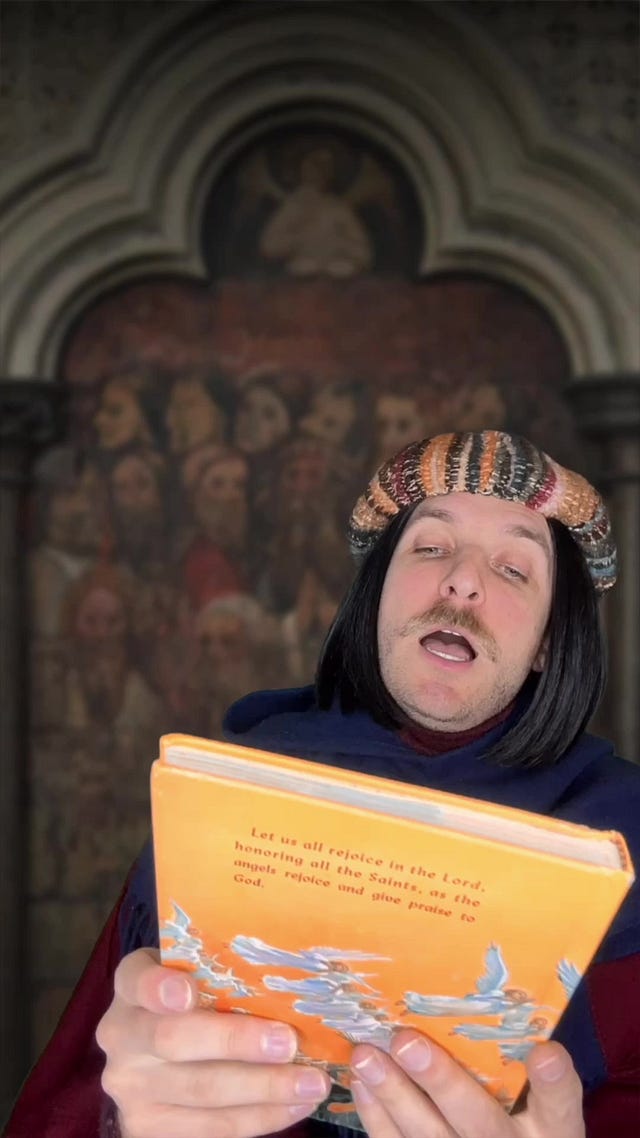

If you grew up, as the French say, catho-catho, then you are certainly familiar with all manners of saint picture books where the saints look like Hollywood Golden Era movie stars, with pained expressions, dramatically staring into the middle distance, wrapped in drapey robes.

Exhibit A (courtesy of Tucker):

One thing that is incredibly accurate from this video is that I, too, thought at age six that stigmata and crucifixions were a lot more par for the course in Christian life than I did at age 16. Or 26.

And now I think they are more common for the saints, but not in the way they appear in treacly watercolor pictures. Reading Dorothy Day’s reminiscences from Commonweal, I saw her stigmata, although it didn’t look like Francis’. “‘My bitterness was most bitter’ over and over again, not at Holy Mother Church, but at the human element in it,” she writes.

Saints, of course, you think, I think, we always hear, are the ones who are filled with joy. And in the United States, a country founded on the prosperity Gospel, we do often confused sanctity with cheerfulness. The blessing of God is supposed to leave you with a million-dollar home, perfect blonde children smiling through veneered teeth, and never, once, are you supposed to be gloomy!!! That’s holiness aka proximity to the Divine and it is indistinguishable from the happiness marketed by Wall Street.

It is true that Love of God cannot leave you miserable. To be in touch with the divine must change something? Rowan Williams writes of John of the Cross picking up a Christ child in the nativity scene, holding the child in close embrace, and then dancing around it in a fit of joy. To that man, God is real and he loves him. It’s that sort of stupid-head-over-heels-in-love with the divine, the ecstasies of love, that seem to mark a saint. But Francis who wept over Christ’s wounds in prayer also bore Christ’s wounds—a stigmata.

What is a stigmata but to feel the bitter cost of sin? It’s so ugly and banal. It festers like an unclosed wound. Dorothy tasted that bitter gall of injustice, felt the sting, lived among people who were every day flogged by it, encountered a church of Pharisees who washed their hands, denying over and over that they, too, were scourging Christ in the poor. And isn’t that the same—different, but the same—as bearing Christ’s five wounds upon your hands and feet?

Rejoice, you who have lost confidence in your certitudes, for you are not alone: Christ is born for you! Rejoice, you who have abandoned all hope, for God offers you his outstretched hand; he does not point a finger at you, but offers you his little baby hand, in order to set you free from your fears, to relieve you of your burdens and to show you that, in his eyes, you are more valuable than anything else.

— Pope Francis, Urbi et Orbi, Christmas Day, 2023

Despite their gauche romance, I do appreciate the books full of poor pierced Sebastians and stigmata-ed Francises, and crown-of-thorns wearing Roses and Catherines for suggesting—in bold, bawdy pageantry—that holiness, that is, proximity to the divine, does not look like happiness marketed by McKinsey.

It means a lot of pain and discomfort and, yes, even dissatisfaction. Bitterness most bitter. It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God. It burns.

But Dorothy—and scads of Catholic-coded Romantics after her—love Father Zosima’s line from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: Active love is a harsh and fearful thing compared with love in dreams.

Perhaps that is because the love of God is the love that carries us through the cross, through stigmata, through the bitterness most bitter. There is no way around it and no denying it. But it is that love that is most real. It is the love that is more real than the wounds. The world is so broken—we are so broken—and yet we are loved by a God so delighted by us that he picks us up out of our cribs, wraps his arms around us and dances for joy like a lunatic. And although you can’t get the bitter taste out of your mouth, there is no other response to that love than to praise.