Rapacious ones, who take the things of God,

that ought to be the brides of Righteousness,

and make them fornicate for gold and silver!

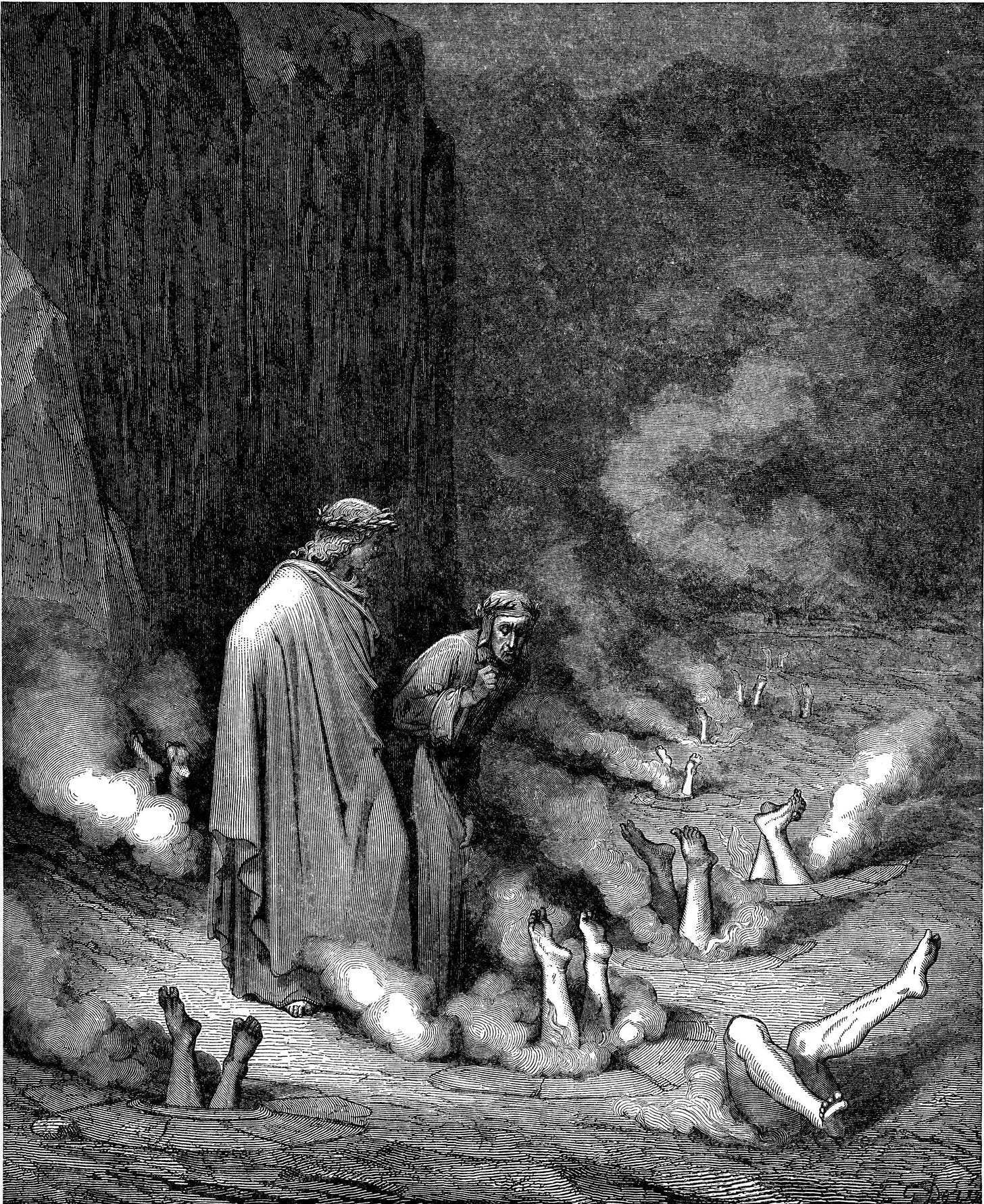

This very evocative passage comes from Canto 19 of Dante’s Inferno. The poet Dante and faithful Virgil are journeying through the large eighth circle of hell, called Maleboge, which are very awful, torturous hot pockets that people have fallen, head-first into.

Maleboge is dedicated to fraudsters, and, in this particular dialogue, that this illustration suggests, this pocket is dedicated to the simoniacs. Simony means paying for sacred things. And its name comes from the poor unfortunate Simon Magus or Simon the Magician from the eighth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles:

When Peter and John placed their hands on them, and they received the Holy Spirit.

When Simon saw that the Spirit was given at the laying on of the apostles’ hands, he offered them money and said, “Give me also this ability so that everyone on whom I lay my hands may receive the Holy Spirit.” (Acts 8: 17-19)

(this will go poorly)

Peter answered: “May your money perish with you, because you thought you could buy the gift of God with money! You have no part or share in this ministry, because your heart is not right before God.” (Acts 8: 20-21)

A-men, Peter. I wonder what Peter would say to the American parish church’s current practice of charging for sacraments.

It is often written down in black and white on flyers as a “donation” but, on internal documents, it is more often listed as a “donation fee” or, simply, a “fee” and is listed among requirements for receiving baptisms, marriages, or funerals.

This is simony, plain and simple. Sacred things are not for sale.

Now, I am aware that churches hire many people who need the basic necessities of life and that the ways of getting that in the 21st century are wages. This is, traditionally, why European churches, with their majestic choral traditions and wealth of art, depended upon patrons for funding.

I am also painfully aware that in the American Church, the majority of parishes in major cities like New York and Chicago no longer operate as missions and instead operate as businesses. Unfortunately, they think first of overhead costs and all the things added under it and then seek the kingdom of God. One can imagine that they no longer ask for true donations or beg for what they need because they no longer have the relationships that ensure that their needs are taken care of. If a church means something to a community, the community takes care of the church or its pastors. Unfortunately, in many places, the church has stopped relying on relationships and instead puts its faith in the security of money.

To start, I find it a bit silly to charge for baptisms, because all the baptized can baptize. It has all the wisdom of charging for the milk of a cow you don’t own. So I suppose you’re paying for a baptismal certificate, which, while a key entry ticket for continuing your life in the church—much as a birth certificate or social security card is for operating in the corporatocracy of the USA—is much beside the actual point of the sacrament.

Charging for a funeral service, when every other cost of the funeral industry is custom-fitted to squeeze every last drop of money out of a family’s life insurance policy is, I think, a flagrant act of disrespect to the deceased and those mourning.

And you may think: Renée, dropping the priest and organist a cool $100 for a funeral service is only courteous. Acts of generosity are good and called for in such moments. But acts of generosity are famously contingent on the will of the person doing the generosity. But when the church institution starts outright charging $400 or $500 for funerals, that’s when you’ve sort of tipped your hand as a Sacrament-dispensing operation rather than a church where believers come to commune with the divine.

And now we come to the most self-defeating and out-of-touch sacramental charges that churches levy: wedding charges. The prevailing logic dispensed from parish wedding coordinators to young couples looking to get married is: “You’re going to be paying for a venue anyway, so why shouldn’t we have a slice of that cheese?”

I get it. The wedding industry in the U.S. generated $57.9 billion in revenue last year. Given that a wedding was a church event before capitalism turned weddings into their own market and we now have Big Wedding, worth billions, selling couples weddings that are, on average, $30,000 to pull off, I can understand why the church feels squeezed out of its own market and wants to recoup a pitifully small amount of that loss as a $1300 charge for a wedding Mass.

The first problem with that argument is that the church has to decide whether it is a market or a mystery. Be a den of thieves of moneychangers or be a temple. You can’t be both.

“No one can serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and money.”

Matthew 6:24-26

Dante felt very strongly about the moneychangers in the church of his day—the ones who bought and sold sacraments and the sacred like it was so much filthy lucre—and he expressed—vividly—what he imagined the eventual end of their actions would be.

The second problem with the current attitude toward marriage is that it shows itself to be remarkably ignorant of the status of religious marriage among the general population. Forty years ago—two generations, when there was still only dial-up internet and cellphones were a dream in Inspector Gadget’s eye—religious marriages accounted for 72% of weddings.

Today, only 49% of weddings are presided over by a religious leader. What the church doesn’t realize is that couples don’t need them anymore—or they don’t think they need them. They can have a friend or uncle get an online certificate and preside at a wedding in a garden, and it is often a lot more pleasant and less hassle than going through church. So, what the church does not realize is that they are not the popular girl in the lunchroom here.

Churches, also, are famously bleeding members by the gallon. So perhaps they could start thinking about how to gain new ones and rekindle a spirit of evangelical welcome and invitation. If a couple shows up at your virtual or physical doorstep, looking to be married in the church, they should be welcomed as a sign of new life, as the precious resource known as the next generation, rather than seen as yet another lemon to be squeezed for financial lemonade.

Churches have no cultural dominance, and so they have very little cultural capital. Therefore, they should remember: they need people and each new person who shows up is a sign of promise and hope that their mission can continue. Perhaps it would be wise, rather than to ask what this new person can do for you, what your church can do for this new arrival. Welcome them into the community, make them want to stay. Isn’t that more valuable than their check?

Couples looking to get married are, perhaps, also in search of meaning, of wisdom and pastoral accompaniment to guide them through this immense step, searching for community in a new stage of life, and these are the sorts of meaning-making and community-belonging that a Church is supposed to provide. The Church is called to see themselves as more than just a discount wedding venue for the spiritually inclined.

And sure, if the couple is from out of town and just coming in because their religious grandmother lives nearby, can’t you still greet them with the hospitality of the saints? We are a universal Church after all—its in the name. Perhaps they will return to their own home and realize that the Catholic Church isn’t just a bunch of child molesters hoarding piles of gold in grand churches for their own worldly glory, but, actually a place of true communion and love, where they, too—and their children after them—can find belonging.

Thirdly, the Church has a mission to the poor. That is the origin of our Catholic schools and Catholic hospitals—institutions that were once such a point of pride—and of most of our urban Catholic parishes.

Marriage, today, is an institution that has begun to be divided between rich and poor, because marriage is now a market, and so the poor are cut out. A recent Pew Research Study on the American Family notes that today, unlike fifty years ago, having a bachelor’s degree indicates that you are much more (17% more) likely to be married than if you have a high school diploma or some high school. Fifty years ago, there was no difference. Both high school graduates’ and college graduates’ marriages were in the 75th percentile. The numbers reflect, likely, both the rising cost and inaccessibility of college and the bifurcation of marriage into a phenomenon that is most affordable and accessible for the upper-middle classes. The problem, of course, is that marriage brings stability and stability brings emotional, intellectual, physical, mental and developmental benefits for the next generation.

If you’re a couple that can afford shelling out $2,000 to a church as a thank-you for all the magnificent work they do putting on your wedding—or just the ordinary work they do—I think that’s phenomenal. And couldn’t your generosity make up for the couple in graduate school who can’t piece that together? Or the parents who already have a child? Or the young couple sharing an apartment but not yet able to “afford” a sacrament?

If the Church has a mission to the poor, then shouldn’t the Church be thinking not how to get a piece of the wedding industry pie, but how to make the Sacraments accessible to the poor—meaning those who are on the edges of the Church, those spiritually poor, and those financially poor? The Sacraments are the foundation of a life, a culture, and a tradition that bring with them stability that could benefit those without a college education, stable housing, or other social privileges.

The Church cannot simply imitate the community and culture-destroying ways of the marketplace around it. It will simply, eventually, fold. It has to let the mind of Christ be in it. A quick glance at the sacrament-selling business seems to indicate the Church has less the mind of Christ about why it’s doing what it’s doing and more the mind of the accountant.

In conclusion, you may think: Renée, you free-lunch-aspirer, nothing is actually free in this life. Au contraire, most of life is free. And, in fact, I would posit that you begin to see the world in two ways, and once you set down on the path you begin more and more to see things only in that light: one is seeing the price of everything and the value or nothing, the other is letting go of the price or the cost, and seeing the thing itself.

I see a lot of worry among people with power that they are being had, and everyone else is figuring out some clever grift to “get something for nothing.” But if I know anything about God, it’s that God is always giving, from the moment we draw breath, and God is not at all worried about giving something for nothing.

“If only we could be what we hope to be, by the great kindness of our generous God! He asks so little and gives so much, in this life and in the next, to those who love him sincerely,” writes Gregory Nazianzus.

There’s nothing worrying about giving something for free. The more you give something for nothing, the more you realize the deepest value of what you have given. To give away something immensely valuable, beyond all price valuation, for free, as a gift, is the most God-like thing we can do. And isn’t the Church supposed to be like God?

Maybe monks and poets know, as Jesus did when a friend, in an extravagant, loving gesture, bathed his feet in nard, an expensive, fragrant oil, and wiped them with her hair, that the symbolic act matters; that those who know the exact price of things, as Judas did, often don’t know the true cost or value of anything.

—Kathleen Norris