“Maybe monks and poets know, as Jesus did, when a friend, in an extravagant loving gesture bathed his feet in nard, an expensive fragrant oil and wiped them with he hair, that the symbolic act matters; that those who know the exact price of things, as Judas did, often don’t know the true cost of anything”

— Kathleen Norris, The Cloister Walk

There is a thin layer of iridescent green-yellow pollen all over the porch, and now Rainy-the-Cat’s fur, and my leggings.

Yesterday, I came out onto the screen porch and three fawns galloped through the garden, scattering at the scent of someone foreign.

One, I think, had eaten the first fig tree buds, the other a daffodil.

In the middle of Lent, my friend Marie-Claire and I did a road trip through the American South, on a journey for her research project on Mary and the Catholic Worker.

Her research is part of a formal project for her post-doctoral fellowship. But I was happy to be along for the ride (and the unofficial driver, since she does not drive) as it was essentially a weeklong retreat on wheels exploring the questions I live each day. Who is Mary? What is Justice? What on earth is the Catholic Worker movement, in all its complexity?

And how does Mary inspire that work?

When I was younger, I didn’t know that Mary was anything more than a statue of Our Lady of Fatima at church and Our Lady of Lourdes at home. And now I feel about her like Gerard Manley Hopkins says: she is our atmosphere. Everything is Mary.

That week, on our road trip, I had to really stop and think: Who is Mary? And why has Mary become who she is to me? On the Rancho’s screened porch, over late lunch egg sandwiches, I recalled for M-C the statue I received of Mary for my graduation from theology school. It came with a small note of commissioning for my vocation ahead. It said that my vocation to write was a fundamentally Marian vocation. To write is to give birth to words and wisdom on the page and in others’ hearts, just as Mariam of Nazareth, Seat of Wisdom, gave birth to the Word.

It is one of the most beautiful letters I have ever received—words of prophecy, words that see things as they are—are always a gift.

Mary is a mystery, and yet she is the mystery all of us—not just writers—dwell within.

As we drove all over the highways and just a few byways along the Gulf of Mexico I thought a lot about subsidiarity—about those closest to the source making decisions. Mary is subsidiarity: what else would you call Marian apparitions? She pops up all over the globe, spreading the Gospel, not through empire or force or power, but by bringing her presence—the one who brings Christ into the world—into all the corners of the world that haven’t ever been touched by Rome.

The Petrine Church’s Achille’s heel is that it loves empire—rule from above, from the center, from the past. Mary gently corrects that fault—she comes to the humble, to the margins, in the present, now. God is here, among us. Here she is, ushering the Word into the world, in the present.

In the middle of our Marian week, we went to a talk on Palestine at a local church. It ended up being mostly a quick architectural exegesis of the Gospel of John. I was exhausted and had trouble listening, but it was beautiful. The Gospel of John is—I've said it once, I’ll say it again—the most Jerusalem-y of the four Gospels. And it merits many talks in many churches to unwind the carefully packed divinity inside each sentence.

When I walked into this church in the middle of Houston, Texas, my eyes locked with an old man I had met in Jerusalem last summer. Was that him? How could he be in Houston, Texas rather than in Jerusalem’s Old City?

And then the lecturer began to speak. He began by saying he, so far from home, was surprised to enter the church and see a family he recognized, who lived right by New Gate. That was my man, I thought, craning my neck and waving.

It was the elderly man who had invited me to his house after liturgy at the Co-Cathedral of the Annunciation in June. This sweet old man—I am forgetting his name—who made sure I had a seat and quwah at the coffee hour after Mass.

I wanted to go up to him, to say ahlan wa-sahlan, to thank him for making me feel so at home, to express that delight and shock that, here we are, fellow pilgrims, meeting again.

There are no strangers in the small world of God.

The sweet man and his wife did not smile like they did this summer. No one said anything of war and terror, but their faces were drawn and worried. They clutched their canes with a worried look. I turned around in the middle of the talk and they were gone. I went outside in the parking lot to see if I could still catch them before they left. But perhaps I will see them again. Perhaps again, in the coffee hour after Mass at the Co-Cathedral of the Annunciation. Maybe they will be able to return to the home they have left. I wonder if anyone is in their apartment now. Or if it is empty, shuttered for who knows how long.

There are no strangers in this small world of God’s. No one is ever as far away from you as you think.

Marie-Claire said that she and I both have “widow pestering the unjust judge” energy. And that is wildly true. Both in a literal sense: we are little critics constantly pounding on the doors of patriarchy. And in a figurative sense: perhaps we pray with conviction because we know that God, like the unjust judge, doesn’t answer right away. But if you are assured of the rightness of your cause, eventually the doors begin to open. A quick perusal of the internet indicates that there is no iconographic tradition of the widow pestering the unjust judge (Luke 18:1–8). And there definitely ought to be. We need her, the woman who prays as all of us ought to—who knows what true prayer is. The woman who knows what true power is.

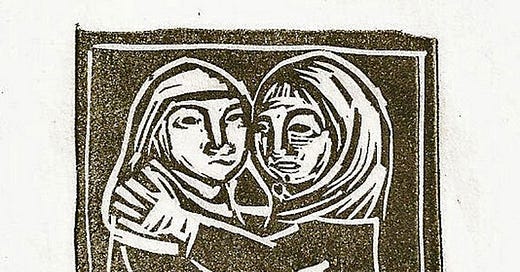

As we traveled all over the low country in haste, I thought of the one Marian story we didn’t talk about that much—the Visitation. We were like Mary a bit that week—showing up on the doorsteps of family members we didn’t even know existed—kindred spirits scattered along the road. And we were embraced by Elizabeths who opened their doors, rejoicing, because they saw Christ inside of us.

The Visitation is the first image of Church. It is a story of sacred hospitality. And it is, in the absence of our friend the widow, a fitting icon for us.

Mary, perhaps like the widow, is assured of the rightness of her prayer. She has prayed and an angel has come and told her God is within her, something that, to most people—to most judges—sounds ludicrous. Crazy. Mary, like the widow, does not have an easy road ahead. But she does not wait to praise God.

And I think that’s the prayer of the widow—it’s the prayer of the poor and it’s the prayer of Mary’s Magnificat—to “thank God ahead of time” as Solanus Casey would say: to let praise precede the blessing, to bless God in the midst of uncertainty. To thank God ahead of time means to have confidence that the one who makes the sun rise on both the evil and on the good, and sends rain both to the righteous and to the unrighteous (Mt 5:45) will take care of us. Because we are creatures and not God.

And so, whatever the unjust judge decides is of really no importance. Because he is a creature, just like you or me, and there is a God who will send rain on the judge and on the widow. And that God is the one to be praised and thanked, no matter the hour, no matter if we have received what we have asked for yet or not. This is the prayer of the widow, this is our prayer.