I, as an elderly man and from the heart, want to tell you that it worries me when we lapse into forms of clericalism; when, perhaps without realizing it, we let people see that we are superior, privileged, placed “above” and therefore separated from the rest of God's holy people. As a good priest once wrote to me, “Clericalism is a symptom of a priestly and lay life tempted to live out the role and not the real bond with God and brethren”. In short, it denotes a disease that causes us to lose the memory of the Baptism we have received.

Pope Francis, Letter to Priests in Rome, Aug 5.

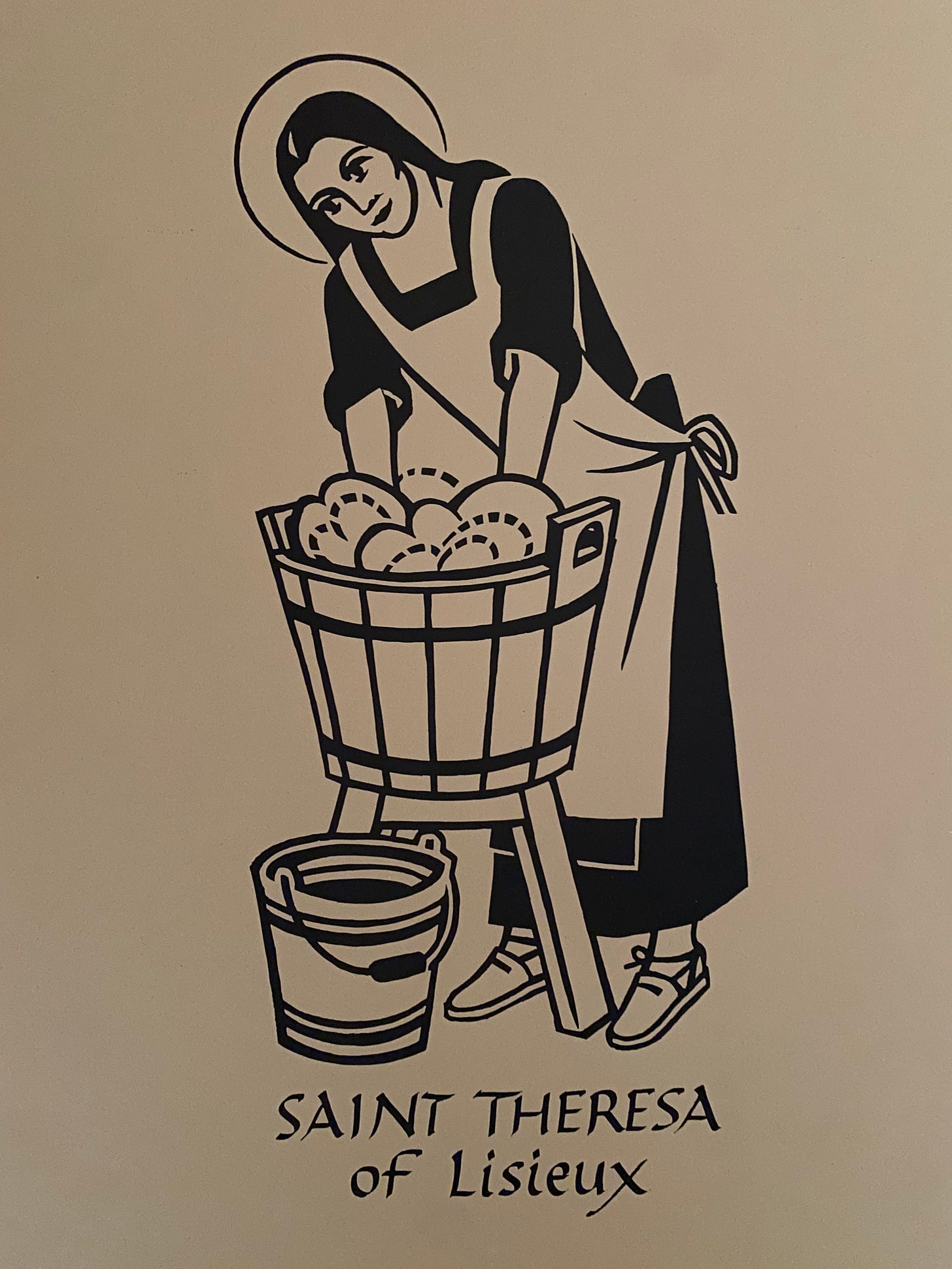

It’s important during these high holy days of harvests (Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, St. Jerome, Michaelmas, St. Therese, Guardian Angels) to really see the faces of the saints and angels being celebrated. It’s so easy to gloss over one day after another. Searching for fall colors, bemoaning summer heat, letting one day slip away into the next.

“Holiness is the most attractive face of the Church,” as Francis says. We have to take the time to see the faces of the holy.

St. Therese of Lisieux is one of those saints I always wrote off as a child. She was too fantastically good. She was too florid and saccharine. Too consumptive. Too nineteenth century.

Plus, in homeschool Catholic land, all the mothers are comparing themselves to the gold standard of Zélie Martin, who raised five girls, all of whom became nuns, four of whom entered the same Carmelite Monastery. (Léonie, the middle child, went her own way and became a Visitation sister. Classic.)

The problem with ideology is that it takes beautiful things and makes them unappealing for the purpose of making a point. Thérèse is one of those casualties.

Then, of course, over time, I discovered that so many of my favorite saints loved her. And so—in American high school movie terms—you realize that the nerdy girl has very popular friends, and you come back around for a second look.

From Von Balthasar to Dorothy Day, models of faith for me in various moments of my life, I found that writers and thinkers who had nothing in common with Thérèse looked to her as a common inspiration. They found a depth in her love, in her short life (which is impossible to appreciate as short when you are twelve, and hard to comprehend just how short it is once you hit 25), and in her simple parsing of the interior life that I am just beginning to see the beauty of.

The saints are too often held up as set-apart, special, and heroic in ways we could never be, so we forget that these most attractive faces of the Church are supposed to be attractive for the sake of imitation. Beauty is mimetic: we want to imitate what we see as beautiful. If this were not so, makeup advertisements would be in vain. We want to look like the beautiful look—including the saints.

Another fact about Thérèse that always trails in her halo of facts and legends like Pigpen’s cloud was the fact that Thérèse wanted to be a priest. So I was thinking of the Little Flower when reading Francis's August 5 letter on clericalism.

It’s a great letter. And if he had written it two months later, I feel like he would certainly have invoked the Little Flower of Carmel as a sure antidote to the “spiritual worldliness…that reduces spirituality to an appearance.”

This spiritual worldliness known as clericalism, he says, makes priests—or, really, anyone in a position of religious power— “men clothed in sacred forms that in reality continue to think and act according to the fashions of the world. This happens when we allow ourselves to be fascinated by [by] vainglory and narcissism, by doctrinal intransigence and liturgical aestheticism, forms and ways in which worldliness ‘hides behind the appearance of piety and even love for the Church.’’”

Really, Thérèse is such a wonderful antidote to spiritual worldliness, because, in fact, her life is a model of the sort of consecration we are all called to as the Baptized. As a Holy People, baptized into Christ’s priesthood, we are called to make the world holy. To love the world as infinitely as Christ has loved it.

Francis continues:

“Instead of living by doctrine, by the true doctrine that always develops and bears fruit, they live by ideologies. When you abandon doctrine in life to replace it with an ideology, you have lost, you have lost as in war.”

You have lost as in a war.

Ideologies and doctrines are very tempting things for people like me, who love to write and—even more—love to be right. Words! Ideas! These are very interesting, malleable concepts that don’t seem to demand anything from us. And can make us sound very clever, to boot.

Ideas don’t call us to any sort of gift of ourselves, don’t call us to receive something so lovely as our neighbor. Don’t always call us to pay attention to what’s outside our own mind.

Maybe ideas do not inherently call us to love others. And yet, I think, words do. Writing is—at its best—an act of love. Making something beautiful is supposed to demand the same sort of attentiveness and care that loving another person does. Thinking and talking are not procedural, algorithmic processes: they are creative actions.

Every worker is called to contemplation, wrote Ade Bethune.

Looking at the sweet picture of Thérèse as Ade Bethune draws her, in her little work espadrilles—peasant sandals of the Basque country—washing the dishes, she is a vision of that contemplative force, that creativity and love that spurs each act of production.

“Man makes nothing that does not serve him,” wrote Bethune. It is a terrible affliction to do work that goes against one’s own good or the common good. I see the Palestinian construction workers building settlements off Hebron Road. They are living a terrible affliction.

We forget, since our labor is bartered away for wages that pay for our “real life,” that our work is supposed to serve ourselves and our communities. Truly it is community that is the only thing worth working for.

All good work is done for a community of which we are a part of, we find meaning in. It is done out of love for the sake of our relationships. Work is supposed to be for our own flourishing as well as others’. Because, in the final count, the only work is love. This is the mystery of Christ’s priesthood, which is the mystery both of our baptismal vows and of the ordained.

when I am in this state of spiritual dryness, unable to pray, or to practice virtue, I look for little opportunities, for the smallest trifles, to please my Jesus: a smile or a kind word, for instance, when I would wish to be silent or to show that I am bored.

—Thérèse to Celine, Autumn 1893

Words are a beautiful work. They are a lovely labor. But they fall short so often. There are often not the right ones. They do not come easily, they do not make something as beautiful as you would like. Words are a gorgeous, worthwhile endeavor, to try to put into thoughts all the beautiful feelings and ideas and sensations that being human means.

But, reading Thérèse’s deceptively simple words, I feel that she has expressed something so simple that all the disciples of complexity and saintly wordsmiths I admire understood. As C.S. Lewis once wrote, in what remains (to me) the best articulation of the spiritual life:

at the very zenith of complexity, complexity was eaten up and faded, as a thin white cloud fades into the hard blue burning of sky, and all simplicity beyond all comprehension, ancient and young as spring, illimitable, pellucid, drew him with cords of infinite desire into its own stillness. (Perelandra)

It will probably take me three times as long as Thérèse to understand that simplicity beyond all comprehension she grasped in her two dozen years. But the only work that matters is the work of God in us—the work of salvation: of the God who became man so that we might become God. We are God’s materials, Ade Bethune wrote frequently. And it is the slow work of becoming love, which we become by loving, that is the primary work of us all.

“There are no events but thoughts and the heart's hard turning, the heart's slow learning where to love and whom. The rest is merely gossip, and tales for other times.” —Annie Dillard

This moved in unexpected directions & was a remarkable thing to read.. thx