the thing with wings

On not just loving, but hoping in, our neighbor with Rebecca Solnit and her new collection of essays for a people in despair

"Make us know the shortness of our life/ that we may gain wisdom of heart/Lord, relent! Is your anger for ever? / Show pity to your servants."

Psalm 90

This past weekend, sipping coffee in my friend’s blissful backyard just a few blocks away from the Thames Canal in Oxford, we discussed how we consume our news.

News trickles through digital streams, it’s not necessarily a well that you go to with your bucket and cup. So if you are online, checking email, reading an essay, clicking a link, you’re bound to catch some news out of the corner of your eye.

It comes tumbling into your lap. Sometimes it’s like that: out of nowhere, a fire can come onto your monitor, and consume your peace of mind and your day.

So, with that caveat, that we live our lives in public, and so if you’re in public, you’re bound to overhear something you didn’t come to seek, I maintain something quite simple: if you are struggling with too much news, you should read the news in print. A newspaper is a great invention. It doesn’t overwhelm you, it can’t send you push notifications. It’s simply there, on your kitchen or coffee table, full of information about the outside world, if you are searching for it.

After a two-decades long experiment, it seems that the digital mediasphere has a rather de-forming effect on how we process news and our world. Facebook and Instagram and Twitter and all such faux public spheres have been a fantastically profitable experiment for a select few. And, of course, they each have had their cultural moment, where, perhaps, their purity and novelty allow us to actually do what the internet has so long promised us: to meet other interesting people.

My handle on Twitter was ReNEIGHimahorse. I refused to clean it up or professionalize it, because Twitter was, at its best, a silly internet forum where ReNEIGHimahorse and Jesuit Space Cowboy hung out. Was it really, could it ever be, something more? Did I want it to be? And if it promised more than just a place for silly nerds to meet one another, would it implode on itself? (History seems to have said: yes.)

At the end of the day, most social media sites are not particularly interesting and they’re not particularly helpful. We don’t really go on them because they are the best reading or socializing we have on offer. We open up their candy-colored app icons on our phone because they have fed us the lie that we need them and we don’t have anything better to do.

When, of course, the world is full of a million and one better things to do: make pesto, clean out the chicken coop, write something, pray, read the London Review of Books (in print), water the fig tree, call a friend, FaceTime a nephew or a niece, play a silly card game, wander into a museum in the middle of a rainstorm, or answer the doorbell and have a conversation you never expected.

And as important as it can seem to stay on the whirligig of news, it ends up being a bit dull and dulling.

We are daily baptized into the chaos of violence. Charlie Kirk, a young father of two and a conservative influencer, was shot yesterday, the same day that a shooter entered a high school in Colorado and killed himself while wounding two othe students. This just two weeks to the day after the Annunciation School shooting in Minneapolis in which the shooter killed two children and himself. That shooting took place the day after another shooting outside of Cristo Rey High School in Minneapolis, which took place less than three weeks after a gunman shot nearly 200 bullets at the Center for Disease Control Building in Atlanta, killing a police officer. In June, a Minnesota state representative was assassinated along with her husband, by a man impersonating a police officer. In April, the governor’s mansion here in Harrisburg was set on fire, and the suspect charged with attempted murder.

Many similar lists include Luigi Mangione, who has been charged with killing the CEO of United Healthcare outside of his Manhattan hotel in December.

For years, sociologists have charted the rapidly eroding trust that Americans have in their own institutions. This distrust has serious consequences, and one of those is increased violence. In a climate of distrust, we choose our own anger and vengeance, having lost all sense of common process. It does not seem like a coincidence to me that the CEO of United Healthcare was shot in the month after Trump was elected—a malaise of despair seeped in with the darkening days and lengthening nights of those winter months. This is exactly the climate which Rebecca Solnit was addressing.

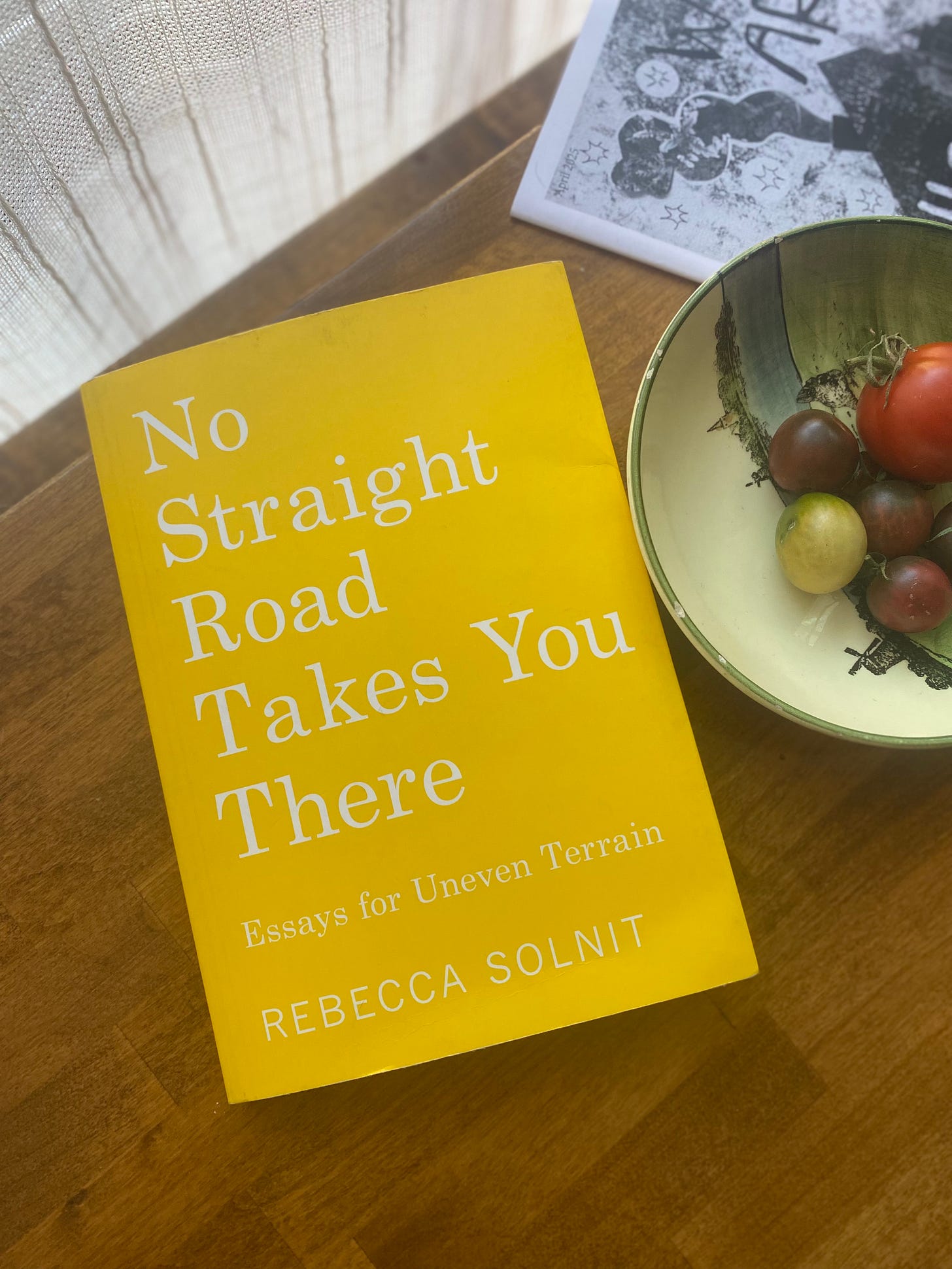

In her new collection of essays, No Straight Road Takes You There: Essays for Uneven Terrain, Solnit describes herself in one essay as the tortoise at the mayfly party. In this digital roller coaster of news, we are often tempted to mistake progress as a sudden burst of revolution rather than a long, slow pilgrimage.

“It takes time to see change,” she writes. “Events, like living beings, have genealogies and evolutions, and to know those means knowing who they are, how they got there, and who and what they’re connected to.”

You have to get acquainted with thinking over time, thinking structurally, accepting that things were not always the way they were now and getting curious about how things came to be this way. We arrive in the world in the middle of the story—its ending depends on what we do here in the middle. “The short view generates incomprehension and ineffectuality,” she writes.

If we feel overwhelmed and lost in the middle of this litany of violence, perhaps, she notes, this is not entirely accidental. There is money to be made from doomscrolling, our glassy-eyed despair is someone’s paycheck. The problem is, despair leads to the violence. Her final essay in this collection is a short credo written a month before the CEO of United Healthcare was shot in New York City. When he was shot, the internet erupted in schadenfreude. Health insurance is a broken system, and many Americans find themselves in crippling medical debt or denied critical care while a select few profit off their pain.

How do we create a society, Solnit asks, where we want the good for the other? Where the idea of profiting off of someone else’s misery or death is unthinkable. We are so far from that society, but bullets will never bring us closer to it. Many of our systems that claim to bring justice seem no more peaceful than a bullet. But that is no excuse to pick up the gun. “There is no alternative to persevering,” Solnit writes, “and that does not require you to feel good.”

Solnit is popular on the internet for coining the Buzzfeed-feminist era catchphrase of “mansplaining.” She, of course, would never stoop so low as to concoct the word itself, a pillar of a fourth-wave feminism, but she did write the 2008 essay “Men Explain Things to Me,” whose insights into the gender relations of the human condition remain as sardonic and insightful as Dorothy Sayers.

In “Are Women Human?” Sayers pokes fun (with a flaming red poker, straight from the fire) at the segregation of women into their own corners of the world. A partitioning off from common human experience, accompanied with the lace-doily condensention that assures women they are fairer, gentler, and, in fact, better, than men so they require their own, softer, gentler space.

This segregation is, in fact, a cunning brutality. On the other face of this gentrified coin lies the incel-like hatred of women, seething under the surface. I recently came across an example of this from a “male Catholic influencer” account called theromanbaron (one of those examples of opening up your phone and the screen going up in flames).

TheRomanBaron informed us:

Women feel so entitled when it comes to men. They do not recognize themselves as sinners just as men do, and they build up a victim mentality, and feel like they are a protected class (because society has made them out ot be.) Consequently, even catholic women are not worth marrying, or dealing with. They fetishize the idea of obedience and tradition, but still try and domineer the man. It’s all a larp.

Well. It would seem chivalry is dead, ladies.

We seemed to have flipped the coin over. “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere/The ceremony of innocence is drowned,” as Yeats wrote in “The Second Coming.” No longer covering up libido dominandi with at least the fig leaf of professing Christian values of mutual respect, the internet reveals that a new rabidity has entered the chat.

Rebecca Solnit takes on the newly brash brutality of the world in her new essay collection No Straight Road Takes You There: Essays for Uneven Terrain.

Solnit is a personalist, through and through, with a Catholic honoring of the dignity of the human person. Of all writers alive, she reminds me most of Dorothy Day: a minister with a pen who hungers and thirsts for justice. She writes scathingly of the crimes of Harvey Weinstein, a sexist system that mutes the stories women could share of violence at the hands of men, of Silicon Valley’s disregard for the common fabric of human relationship, of the deforestation of the earth and of gluttonous egos that grow at the expense of others.

Solnit’s goal—and this goal she states with the pure-hearted innocence of sanctity—is to create a world where “the desire and entitlement to commit sexual violence wither away, not out of fear but out of respect for the rights and humanity of victims.”

And, one might add, out of respect for their own humanity. To believe in the goodness of the human person—aggressor, oppressor, the dominator, the abused and the oppressed alike—is one of the most radical acts of faith possible.

In her essay, “Insurrectionary Aunthood,” Solnit uses the relationship of extended family, a gaggle of aunts, as an image of thise sort of society where the dignity of the person, the respect for one another, and love for them is at its center. Echoing the words of Dorothy Day on the Mystical Body of Christ, she writes:

What is mutual in mutual aid is not in the goods and services delivered; it's in the underlying belief in the deep connections between those who give and those who receive. It is a deep belief in and commitment to inseparability: that my well-being is inseparable from yours and that, in caring for yours, I care for myself and, more than that, for the larger whole that is us, because we are in this together. That is, we are not mutual because of the exchange of aid; we aid each other because we are already mutual.

“Hope is a risk,” she reminds us, in her essay titled “Despair is a Luxury. “The future has not yet been decided, because we are deciding it now.”

Solnit reminds us that goodness is not as obvious as an Instagram post; reward for our labors cannot be counted as so many likes on a picture. Progress doesn’t come with instant gratification, because it doesn’t feed our egos. The goal of striving for justice is more about our neighbor and less about our own glorification and aggrandizement.

Heroes are often worshipped, but when we admire the saints, it is more like looking through a window than a mirror. Saints are emmisaries among us from a deeper, richer world than the one glittering around us in pixels. They are like trees whose roots gather water flowing below our feet. When we rest in their shade, we absorb a bit of that world that is their native land. Another world is out there, beating inside the hearts of men and women who look no different than you or I. The bricks to build it are hidden in the hands of each human person, the hands we grasp as we pray the prayer of unity at Mass, “thy kingdom come.” There’s no building it without you. The point is to get there all together, anyway.

Imagine, Solnit says, a world in which no one wants to rape anyone. No one possibly could ever even want to shoot someone. Such desires are shadows and mist, spirits that possess us, that strangle the real breath of life within us. Our real selves are the selves that yearn for goodness. She believes that, all evidence to the contrary. Having considered all the facts, as Wendell Berry says, Solnit still believes that each person can become that real self—it is always possible for a person to let go of a death grip on their will to dominate and become, instead, a person.

To the person who strikes you on one cheek,

offer the other one as well,

and from the person who takes your cloak,

do not withhold even your tunic, Jesus says in today’s readings from the sixth chapter of Luke’s Gospel. That seems like foolishness, but perhaps it is permission. Permission to be our real selves, the selves that want to honor our own dignity and that of our neighbor, in a world that wants us to punch back. Perhaps this is a message of liberation.

Perhaps the chokehold violence has on us is not the last word. What happens when we turn our cheeks, stop judging, give to those who take from us, and be merciful as God is? Jesus doesn’t say. But this is what hope demands: the unavoidable, world-saving risk.

In the morning, fill us with your love;

we shall exult and rejoice all our days.

Give us joy to balance our affliction

for the years when we knew misfortune.

Thank you. The combination of writing lucid writing about Solnit's is just what I needed. And the insight about being given permission to choose our authentic goodness is one that I will take with me.

Absolutely beautiful, thank you...